Designing in our neighborhoods, for our neighborhoods

A Q&A with D.J. Trischler, neighborhood designer, University of Cincinnati professor, and publisher of the Claypole Commons

I first met D.J. Trischler through this very newsletter. During our earliest days at Connective Tissue, D.J. was so active in commenting on and sharing our work that I felt compelled to reach out and learn what the heck he was all about. We scheduled an intro conversation, and a few minutes into it, I came to realize that D.J. is pretty awesome.

Not only does he have good taste in writers (cough, cough: Wendell Berry), he’s also a designer and University of Cincinnati professor focused on the intersection of graphic design, participation, and neighborhood connection. He explores how graphic design influences our experience of place, all centered on one guiding question: How might we use design to connect people to their local ecologies? For D.J., this isn’t just an academic exercise, it’s a lived, daily practice. And the coolest way he puts theory to practice is by publishing the Claypole Commons, a beautifully designed print newsletter exclusively for the 25 people on his block.

Today’s Q&A with D.J. touches on a little bit of everything related to his work. We discuss what happens when neighborhoods are designed for outsiders versus insiders. We talk about his initial inspiration to start the Claypole Commons and his intentional approach to designing and distributing it. And we explore the changes he’s already noticing on his street since beginning to publish the newsletter earlier this year.

I came away from our conversation believing that there is something radical in what D.J. is doing. In publishing Claypole Commons the way he does, he’s intentionally choosing slowness over efficiency, “thinking small” over “dreaming big,” and designing for a particular place over any place. For D.J., it is in this particularity — in this commitment to the proximate — that the seeds of agency and hope can take root.

-Sam

PS: If you’re interested in starting a newsletter for your neighborhood — or if you’re already running one — D.J. would love to hear from you. You can reach out to him directly at trischdj@ucmail.uc.edu. And, if you want to learn more about D.J.’s work, you can check out his Neighborhood-Centered Design website.

You have a fascinating set of interests that sit at the intersection of graphic design, participation, and the experience of neighborhoods. What got you into this work in the first place?

I grew up in Pittsburgh, which is a really interesting place. I didn't know it was an interesting place, though, until I got to my 20s and studied design, and I realized, “Oh, wait a second. Everything is black and gold in Pittsburgh.” It’s on the police cars, the city government, the fire trucks, the sports teams, the bridges. I realized the city was using color in this way to create social cohesion. Somehow, it doesn't matter what your religion is, it doesn't matter what your identity is. When you put on black and gold, everybody knows you’re a Pittsburgher and you respect one another and you cheer for the same teams. I find that so interesting: it's a graphic symbol through colors — two regular old colors.

People really love Pittsburgh. They really, really, really love that place. Now, anywhere I live, I want to fall in love with the place. I suppose that, in part, sparks from going to Steelers, Penguins, and Pirates games with my dad growing up.

You just used the phrase “fall in love with a place,” which I really like. What does it actually mean to you to fall in love with a place?

I like to care for the places I live and pay attention to them and be a part of it. I like to know others and be known by others. To have that kind of connection like, “Oh yeah, we're both from Pittsburgh,” or “Oh yeah, we're working together to make this place better” — that seems like community to me. I feel more fulfilled when I’m connected to the places I’m living and working towards the betterment of those places.

How would you describe your approach to the work of graphic design in neighborhoods? How does it differ from how graphic design is typically deployed in neighborhoods today?

I was reading an article the other day about place branding. There was a neighborhood in Denver being compared to one in another part of the world: while there were certainly uniquenesses to the identities, both neighborhoods almost looked like they could have been for any place.

It's hard to visualize “a neighborhood” because we’re abstracting this really complex thing. I'm interested in this friction. My neighborhood in Cincinnati alone probably has 17 different micro-communities and 17 possible ways to represent the place. I think it's an impossible task to visually identify a neighborhood or a city. I’m not saying we shouldn’t try it, but we're never going to claim it. When we do attempt to visually identify a neighborhood, we also need to be careful about who's represented and who’s not. Place branding might not be the ultimate cause of gentrification, but it certainly plays a part in it.

This gets back to the question about loving a place. Are neighborhood designers coming into these places from the outside? Are they a part of the communities where they live? Do they really know what it means to love and care about a place? Or do they treat designing places much like a commercial design project, where they are doing what the client wants or caught up in current trends?

I'm trying hard to be a member of my community so that when I design with communities (including my own), I know what it's like to be a part of one. This desire grew from my graduate thesis research into neighborhood-centered design in mine and two adjacent neighborhoods. I think that there's something especially important about being a designer for the neighborhood in which you live and having to face the consequences of what you design, or hear the feedback from your neighbors. Being a “member” means that you belong to the place, and the place belongs to you. We could probably go on about Wendell Berry for a while, but in Jayber Crow, he was a member of that town. If he made a mistake cutting hair, he was going to find out about it. There's going to be some gossip.

Can you speak more to why these insider versus outsider distinctions matter when it comes to neighborhood design? How does it affect the look, feel, and overall experience of neighborhoods, both for residents and outsiders?

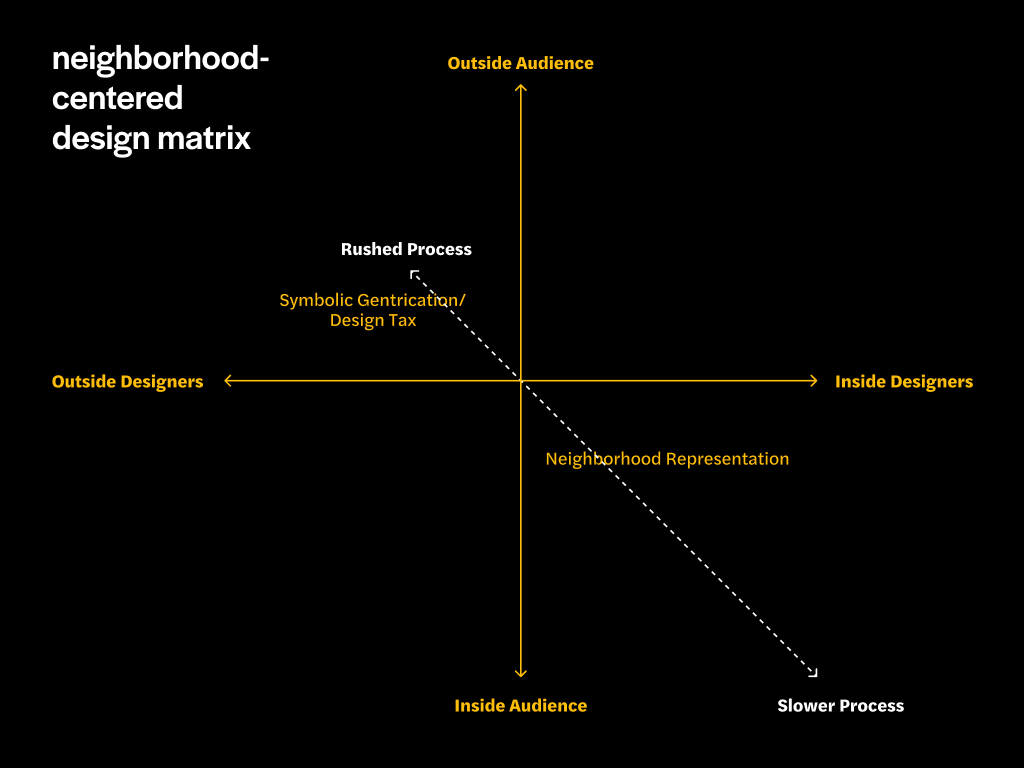

I'm picturing a two by two matrix. On the horizontal, it’s asking: “Who am I? Am I an insider to the community or an outsider?” And on the vertical, it’s asking: “Who is this for? Is this for insiders to the community or outsiders?” Maybe, there's a third dimension about the project timeline. If we were to look at that 3D two by two, I imagine that a lot of new neighborhood brands look like they’re “by outsiders, for outsiders.”

And what happens to a place when it’s designed for outsiders? A blandness starts to show up. Visual identities for particular places start to look like they could be for any place. Neighborhoods start to mimic what other “successful” neighborhoods have done. You go to these neighborhoods and they have flower shops and coffee shops and eateries and all these things that developers know are safe and that people will want. They don’t exist much in my neighborhood, and I wish they did a little bit more. But I don’t want my neighborhood to look like the neighborhood across the river. I want it to be somewhat unique. I want it to reflect what our population brings to this particular place.

This also relates to symbolic gentrification, where new symbols (of wealth) replace old symbols — and the new symbols look less affordable and inclusive than the old ones. The neighborhood I live in has been an “affordable” neighborhood in recent history. A lot of people move here, not because they maybe wanted to, but because it was the only option. But as it develops, will the grocery stores and business districts look like places that include the current populations? Places that have the designerly touch often come with a design tax: you're going to pay more to visit these places because they’re designed. My wife and I used to get so mad about the design tax (even before inflation), but now we just accept it. We accept that when we’re going to go out to eat in a “cool” neighborhood, we’re going to pay the design tax.

We’ve been hovering around this idea of memes and memetics this whole conversation. The way neighborhoods replicate certain types of coffee shops — it’s such a meme. But the same thing can happen with gardens. If I start a garden, it’s more likely my neighbors start a garden. If I put myself out there through my newsletter, it’s more likely my neighbors will put themselves out there. We need to choose our memes wisely, and maybe that means putting ourselves out there first.

I’m glad you’re getting to how you are walking the walk and putting yourself out there through your new, print newsletter. It really seems like your passion for design, place, and community has found an outlet in your neighborhood newsletter, the Claypole Commons. Can you share about the newsletter’s origins?

I’ve always found newspapers to be really fascinating, accessible sites of design. Anybody can pick up a newspaper and read it, and even more so with a newsletter. It’s just a sheet with a few paragraphs of text. Ever since my graduate studies, I’ve been sitting on this idea for a one-page, printed newsletter for my block that could be a site for design and connection. But I never acted on it.

Then, earlier this year, we had a shooting on our street. Immediately, I thought this could go one of two ways. We could all close up our houses and buy security cameras and not talk to each other. Or, we could decide to come together. The pandemic taught me that the better I know my neighbors and the more belonging I have in a place, the safer I feel and the happier I feel. After the shooting happened, I decided that I could help bring people together by launching the newsletter.

In my initial visioning for the newsletter, I kept returning to this concept I’m really intrigued by called latent neighborliness. Basically, it’s this sense that you have positive feelings for your neighbors even if you don’t hang out with them or have parties with them. Latent neighborliness leads to people actually having your back without creating any of the pressures to perform. I didn’t want to create a newsletter about the people, because I didn’t want people to feel this pressure to perform neighborliness. I just wanted to create a newsletter to help them connect with the place. And what do we all have in common on our street? The land. We can either choose to make our lives on this land better, or we can make our lives worse.

So I’m in my yard, tending to my garden, and I start thinking, “What if this newsletter was just about what’s happening in nature? What if it’s just about calling attention to the things occurring on our street that people often don’t see?” That was my “aha” moment for what the newsletter would actually become.

That’s a powerful origin story. What does this approach to designing and publishing the Claypole Commons look like in practice?

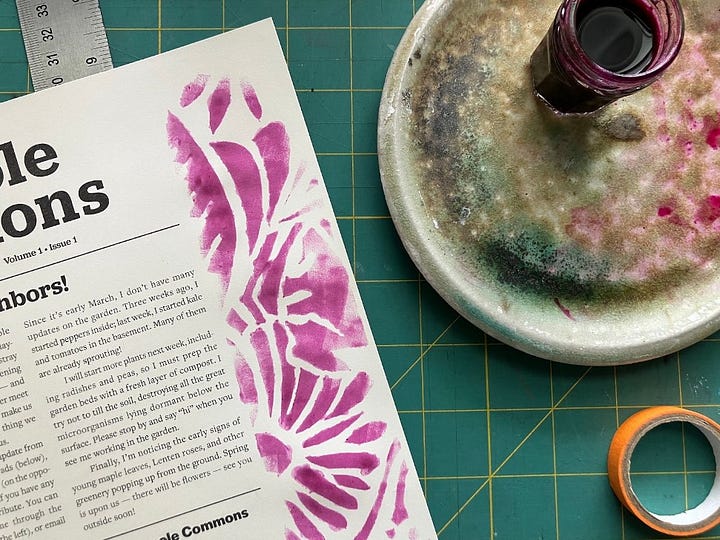

Design-wise, I just started eight months ago with some simple type. I picked a couple of typefaces that I didn't think were too stylistic, but I also considered some of the typefaces I had seen around the neighborhood. I applied design principles because I want the newsletter to be legible. I also want it to be attractive so that people read it and don't just throw it away.

Recently, I've started adding artwork — usually, it reflects the season. This current one is going to have a big monarch caterpillar because they've recently been in our yard. Last month, I got some ink from the pokeberry bush in the back, and I stamped every newsletter individually with a cool design. The ink was from this particular place, and the stamp was connecting people to the pokeberry they may have in their yard.

The content is also connected to the nature on our shared street. For instance, I’ve been thinking about the next issue. I might talk about our “wild neighbors,” as David Klein calls them. When the cardinals start chirping at 6:30 in the morning, the rooster starts crowing at 6:00, followed by the titmice. Or maybe I’ll talk about the goldenrods about to bloom and then the asters coming soon. These things don’t feel so pressure-filled to talk about, right? So, now, people talk. Neighbors will just come up to me and ask: “How do I get some sunflower seeds?” Or, “How do I grow this plant in my yard?” It’s not an interview or a survey. It’s just a conversation.

On a related note, my wife and I have been hosting an event on our street every month. Last month, I made a hand-printed poster for “Meet the Chickens,” and we had people come over to meet our chickens. We had three new chickens. We made a little sheet and had people name the chickens. We didn't vote. We just came to the conclusion that we were going to name them Richard, Dolly, and Penny. My wife and I take for granted that we know everybody on the street, but not everybody else knows each other. Something really cool happened at that event: we were sitting at a picnic table, and people were asking each other, “Who are you?” Seven people showed up. But it lasted an hour, and we all connected.

The whole Claypole Commons newsletter seems like it’s an act of attention and noticing. I know it’s only been six months, but have you noticed any changes — or signals of change — to your neighborhood since you began publishing Claypole Commons?

My wife and I have been keeping a journal about life on the street. It's inspired by Wendell Berry and others who pay attention to the “mundane” and are telling stories about everyday life. Since launching the newsletter, we’ve started hearing a lot more from neighbors. People will talk to us and address us by our names without us reaching out to them, like: “Hey, DJ! Hey, Megan!” Megan heard a neighbor once say, “Those two are so cool, they have a newsletter.” And people have started trusting us as neighborhood stewards — they’ll come to our house and drop off compost, and they’ll share stories with us that we’d never heard before.

There are really explicit things that have happened, too. We have a WhatsApp group now. One person has started putting footage that they've captured from a bird feeder camera. People are also asking for help in the group, like “Hey, do you have some sugar?” Or, “Hey, did the rain affect you last night? Hey, there are some dogs running around the street, what's going on?”

Personally, one of the cooler things that has happened is that I've learned my neighbor can fix bikes after he’d been coming to the compost pile for a while. Recently, he's fixed both Megan’s bike and my bike. I asked, “Can I pay you back for this?” And he said something along the lines of, “We just love being a part of the ecology here.” And the other thing he said was, “We think we want to get bees so we can contribute to the street.”

I feel like The Claypole Commons is becoming this cohesive symbol for the neighborhood like Pittsburgh’s Black and Gold. There are only 25 houses we give the newsletter to, and we're all a part of it. People are starting to see themselves in it — even if it's not explicit — and it feels like there's more connection in the place. People are starting to feel like we're a community here.

If we go back to the two-by-two, I'm designing inside my community for inside my community.

There's something really radical in what you're doing. It strikes me as intentionally slow, intentionally small, and intentionally specific and particular. I’d be curious for you to reflect on that. Why does this slow, small, particular, and hyper-local work matter?

I think there's a part of me that really wants to be radical — but I'm not.

When I think about all the things I'm doing, I'm most excited about seeing monarch caterpillars on my milkweed plants. I’m most excited about seeing neighbors talking to each other and exchanging eggs or baked goods or seeds instead of buying them. I feel like going slow invites more people in. It keeps me in check. But it also feels like we can have these small victories — these small victories that keep us going.

The commons were a place where you went to find firewood. They were a place where you went to plant a garden. They were a place where you met your neighbors and helped each other out. I like that we occasionally have that feeling that the commons still exist. I don’t want to get overly spiritual, but Wendell Berry ends Jayber Crow by saying, “Maybe this was really about heaven.” Sometimes I think maybe heaven does exist on earth on Claypole Avenue — and it’s in these particular moments of small exchanges.

Your answer reminds me of a Wendell Berry poem that my friend Pete Davis recently introduced me to:

“In the dark of the moon, in flying snow, in the dead of winter,

war spreading, families dying, the world in danger,

I walk the rocky hillside, sowing clover.”

We’re all walking the rocky hillsides. But to sow clover there, too, that’s an act of hope.

this is so inspiring! now i wonder: what would prevent most of us to start such hyper-local newsletters in our own neighbourhoods?

A sweet ray of winter light. I've noticed that a neighborly effort to have people mingle (e.g., cocoa in the cul-de-sac) usually lasts only as long as the event, and then we disperse. Maybe a newsletter is the answer, or at least a part of the answer. Wonderful interview.