How libraries can become hubs for civic life and social connection

A Q&A with Shamichael Hallman, author of “Meet Me at the Library” and Director of Civic Health at the Urban Libraries Council

Shamichael Hallman is the Director of Civic Health and Economic Opportunity at the Urban Libraries Council and is the former Senior Library Manager of the historic Cossitt Library in Memphis, TN. He recently published a new book, Meet Me at the Library, which sees America’s public libraries as one of our best hopes for connecting across lines of difference and cultivating stronger communities.

My conversation with Shamichael was full of tangible examples of what libraries’ civic potential looks like when it’s realized in local communities. It’s a fun, practical read that will energize true believers in the civic power of libraries, and may even change the minds of some library skeptics, too. And if you enjoy the Q&A, please consider supporting Shamichael by buying the book or perhaps checking it out at your local library 🙂

- Sam

You published your new book, Meet Me at the Library, just this month. What’s the story behind the story? How did the idea to write this book come about?

In 2017, I was hired by Memphis Public Library to oversee the renovation and reimagination of the Cossitt Library Branch. This was the first library in the city. It was located In the heart of downtown Memphis right on the Mississippi River. It had such a rich history, but it was in need of new life.

A big part of my work with reimagining Cossitt involved inviting the community in. Within the library’s strategic plan was this idea of the library's role as a community anchor and catalyst for civic engagement. In particular, we had this vision to develop programming designed to bring together diverse groups of citizens who otherwise might not have an opportunity to interact with or learn from each other. This ended up connecting to the work of Reimagining the Civic Commons — a larger initiative that was focused on strengthening the civic infrastructure of Memphis and four other communities, particularly by promoting social mixing within public spaces and encouraging civic engagement in these spaces. Everything we did to renovate Cossitt tied back to these two goals of mixing and engagement.

Through this work, several opportunities emerged for me to speak, particularly about the role of libraries and public spaces in addressing social isolation and political polarization. These were sometimes at the local level in different cities and sometimes at the national level with different organizations. But throughout these conversations, libraries felt like an afterthought — and I saw the need to more assertively affirm the role of the library. There was a real opportunity to bring library leaders and civil society leaders into conversation with each other to talk about the value of the public library to strengthen the social fabric. It was these conversations, coupled with my work to reimagine Cossitt, that inspired this book.

What are some tangible examples of the particularly innovative work you did in Memphis around civic engagement?

The design of the space really mattered. We, the library staff and the designers from Groundswell Design Group, did a lot of deep community engagement, asking community members: “What could you imagine this library to be? What do you need this library to be? And how could we shape this library so that it would have a direct impact on your daily life?” With the design, a couple of things happened. We opened the space up. We got rid of the classic library design of having immovable wooden shelves; instead, we installed shelves that were movable so that, on any given day, you could reorganize the library differently based on what the community needed.

We also programmed the space to align with community members’ interests. Because of where the library was situated, we thought we needed to add a cafe because there were not a lot of food options in the neighborhood. In the design phase, lots of people shared things like, “Hey, I'm a maker. I create things. I make soaps. I make jewelry. I make shirts. It would be great to have a maker space.” And so we embedded that into the library, too. We ended up with this space that was very flexible, multifunctional, and met the needs of lots of different users.

Beyond that, we got very creative with the art. Not only was it the first library in the city, dating back to the late 1890s, but it was also a segregated branch that Black people couldn’t access for almost 60 years. We said, “This is an integral part of our history. We’re not going to wash it away. We’re going to use art to elevate the story of Black people who came to the library and held the sit-in demonstrations that ultimately led to the desegregation of the library system.”

I’ve heard you say before that libraries are more than just repositories for books. What is your ultimate vision for libraries in civic life? How have you seen libraries begin to step into this role?

The library is an institution that has always been evolving and always finding ways to adapt to whatever is happening in society. We really need to lean into this history. We have to be mindful of what is happening in society and ask ourselves, “What is it that libraries must do in this moment?” Along those lines, there are really two practical questions underpinning this book: (1) How can libraries help relieve social isolation? and (2) How can libraries increase levels of civic engagement?

In terms of civic engagement, libraries can be a space to educate Americans about how their government and community actually works. When you think about the collections libraries have, the books they offer, and the programming they can host, there's a huge opportunity for libraries to step into a role of promoting lifelong civic learning. Libraries can also recommit to their histories as civic incubators within communities and discover a more intentional role as a social connector. Libraries should actively be cultivating the civic knowledge, civic attitudes, and civic behaviors of their communities, which they could do in so many ways — whether it be through their design, their collections, or their programming, for instance. Salt Lake County Public Library’s “Let’s Be Neighbors” program is a great example of this civic work in action. They host conversations on a range of topics that are of local interest (e.g., drought, housing), feature local experts, invite the community to engage in robust discussions, and provide concrete steps and resources to take civic action.

When it comes to reducing social isolation, libraries have an opportunity to become spaces where people can encounter and have shared experiences with neighbors along with those they wouldn’t otherwise meet. Libraries have virtually no barriers to entry — there's no cost and there's no belief system that's required for you to participate — you can just be there and be in community. Still, libraries need to get better at measuring social connectedness. Right now, it’s hard for libraries to get data about who they are serving and where these people are coming from. But we have to determine how we can use data to understand if we're actually serving all the people that we think we're serving.

The vision for libraries also has to be multifaceted because libraries serve so many different audiences who are coming in with different needs and hopes. So that vision must ultimately be one that's rooted in the local context, maybe even the hyperlocal, neighborhood context. Cambridge Public Library’s “Cambridge Cooks” program, for instance, brings in local chefs to provide free cooking classes for neighbors — many of whom are immigrants — to come together in community over food and shared meals. Libraries that are rooted in their neighborhoods are uniquely positioned to do what Cambridge Public Library does and respond to their neighbors’ needs.

Despite their promise, libraries are still mainly used by people with college degrees. I know accessibility is a big area of focus for you, both in your writing and your day-to-day work. Where have you seen libraries be particularly effective at working with community members who may not have degrees?

I need to start with my experience in Memphis — that was ground zero for me. Memphis is a city where maybe only a quarter of the population has a bachelor's degree. Probably a majority of the people who are coming into the library are folks who don't have that college degree, but still come from many different walks of life. Some of them might be lifelong learners, getting access to books and using numerous databases. Some of them might be trying to create a business plan or learn a new skill or get a certificate or increase their employability. Some of them might be mothers who are coming for storytime. Some of them might be unhoused people who are coming for shelter or to find out about what services they can receive. There are all sorts of things that are happening.

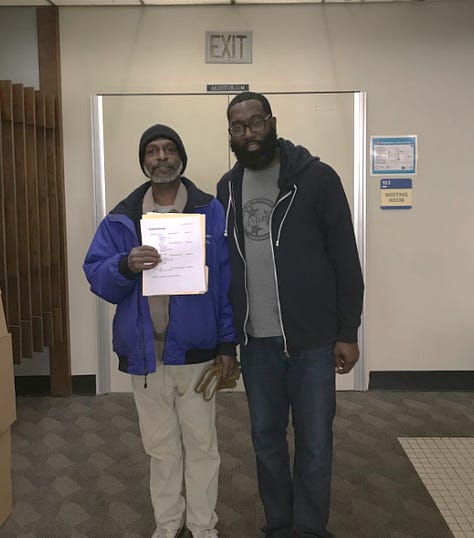

Let me share one of my all-time favorite moments from working in the library. A gentleman I call John came in one day looking for help applying for a job at a local hotel. The application had to be submitted online, but John didn’t have an email address or a résumé. Over about an hour, we worked together to create both. I asked him to write down all of his job experiences, listing everything he could remember. Using that information, we downloaded a Microsoft Word template and built his résumé together. As we worked, I explained each step and created a relationship and dialogue that guided him through the process. Once his résumé was complete, we tackled setting up an email address, and then created an account on the employer's website to submit his application. John thanked me and promised to stay in touch.

About a month later, he returned to tell me he’d actually gotten the job. I was so excited — both that he got the job and that he thought to come back and tell me. This may just be one story, but libraries and their staff are providing invaluable support like this every day.

That’s a beautiful story about the importance of interpersonal relationships to the success of libraries. I’m also thinking a bit about what individual libraries and library systems can do. What are you seeing libraries do to begin overcoming some of the broader socioeconomic barriers to access?

The opportunity for socioeconomic mixing lies in undoing the economic and racial sorting that has been designed into our communities. Libraries are recognizing that not only should the central or the main branch be this wonderful space that is attracting lots of people, but that the other branch libraries throughout the system should also have a destination quality to them. There should be something about the neighborhood branches that creates that “wow” factor and encourages people from across the city to visit. Maybe it's a special collection. Maybe it's some sort of equipment that's there. Maybe it’s a maker space or a co-working space or some sort of art exhibit.

The Chicago Library System is doing this very well. They have a program called “Culture in My Neighborhood,” which essentially is an invitation for residents to visit all of the library branches in Chicago. Programming is compelling and reflective of the local neighborhood, ranging from cultural performances, to arts workshops, to walking tours of historic branches. When you offer that invitation and when you design your branches to have this destination quality, you have the opportunity to bring in people who are coming from the other side of town.

Because public libraries are funded by the local tax base (at least, in part), more well-resourced places like Cambridge tend to have more well-resourced libraries. So, what are the implications of this dynamic for rural areas and small towns — or even struggling cities — that may have much smaller library budgets? What are those places doing to promote accessibility for their communities and the quality of the library as a civic asset, particularly when those resources are less abundant?

I love what the North Liberty Library is doing in North Liberty, Iowa. It's a library system of one, and its success has been driven by its leader, Jenny Garner. She knows that she has to be her library’s fiercest advocate. She’s actively communicating the value of her library to the Mayor and City Council: not only is she hosting meetings with them, but she’s also inviting them to come to the library and participate in its programming. Library directors — particularly in these smaller and more rural locations — must be like Jenny and effectively engage and get buy-in from local leadership.

But the leader also needs to be able to effectively connect with the community. This means going after $5 to $10 grassroots donations from community members. This means securing local partnerships to supplement the library's limited staffing and resources — partnerships ranging from workforce development and entrepreneurship initiatives to summer literacy programs. The libraries that are thriving right now tend to have a table that's wide enough to invite all sorts of partnerships from the community. And by partnering with community groups and hosting events at the library, these leaders can bring in new audiences who may not otherwise see the importance of their local library.

With the Urban Libraries Council, we’re also seeing this bubbling up of partnerships between urban and rural libraries. In the Kansas City region, we’ve been working with three systems that span all parts of the region: the Kansas City Public Library, the Mid-Continent Public Library, and the Johnson County Library. All three have different and complementary resources to help support entrepreneurs. For instance, the Kansas City Public Library has this beautiful space called One North that’s free and is nicer than any co-working space where you’d spend $400-500 per month. The Mid-Continent Public Library has a Culinary Center: on the public-facing side they do cooking demonstrations and skill workshops, and on the back-end, they have a space for food entrepreneurs to prep, cook, and store their food. Then the Johnson County Library has an amazing MakerSpace with sewing machines and fabrication machines and 3-D printers and laser engravers and cutters. They've got a plethora of laptops that have creative software for podcasting, music, production, and design.

And what we’ve said to all three of these libraries is, “Hey, perhaps the best place that you could refer someone to for entrepreneurial support is the other library system.” Now that these inter-library partnerships have started, they have connected people and organizations in all parts of the region that hadn’t previously been connected.

Let’s say someone reaches the end of this Q&A and is still skeptical about the role of libraries as community anchors. What’s your case to convince them otherwise?

Beyond their individual benefits, libraries can strengthen entire communities. More and more libraries are promoting a circular economy. You can go and check out a fishing pole. You can go and get car diagnostic tests. Instead of buying those things, you can go and grab them from the library. Libraries are helping us consume less and share more.

The library is also a place where people can go to become a better version of themselves. You can go to the library and learn new skills — to increase your employability, perhaps, or to go deeper in a new hobby. I feel like, man, we all need a hobby in this day and age that we're in. The possibilities at the library are endless. I can pick up a camera and see what I can do. I can pick up a sewing machine and see what I can do. I can even take up calligraphy. The library is a place where you can find resources and programs to be able to do those things, and again, it won’t cost you a thing. These things make a community an even better place to live and stay.

Absolutely love this!