Building tech that's relational, place-based, participatory, and ~weird~

A Q&A with Josh Nesbit and Deborah Tien, co-founders of the Relational Tech Project

This week’s interview is with Josh Nesbit and Deborah Tien, co-founders (along with Sadev Parikh) of the recently launched Relational Tech Project (RTP). In their words, relational tech “reconnects us with the people around us in the places where we live,” helping people “care for each other, collaborate, and build trust.” With RTP, Josh, Deborah, and Sadev are focused on “building and supporting builders of village-scale tools that strengthen relationships in neighborhoods.”

As it turns out, Connective Tissue served as the actual connective tissue in RTP’s founding story. While I had known Josh, Deborah, and Sadev independently from different parts of my life, they all first met at an informal and ~emergent~ retreat that Connective Tissue hosted back in May. As you’ll read, the three of them self-organized into a session around “pro-social tech,” and within two hours of meeting each other, they hatched the idea for what is now the Relational Tech Project. I distinctly remember Josh coming up to me after that first session and saying, “The three of us are going to build something together.”

Four months later, they have built something — and it’s really cool. So, I wanted to sit down with them to learn more about the project and to explore some of the more countercultural questions they’re raising. What does it look like for tech to be in the service of relationships instead of replacing them? How can tech become an avenue for active participation, rather than passive consumption? And how can tech be built at the block, neighborhood, or community scale, rather than the homogenizing platform scale that’s predominated the last several decades?

This was a fun, playful, and, most of all, weird conversation in the best way possible. If you’re interested in learning more, please consider giving the full interview a read. And if you want to get weird with Josh and Deborah, consider heading over to the RTP website to join a network of people building and “remixing” relational tech.

-Sam

… but wait, before you jump into the Q&A, we have two fun and relevant announcements:

Microgrants: Applications for our neighbor gathering microgrants are due by EOD tomorrow, September 24th. If interested, apply here!

RTP AMA: We’re hosting Josh and Deb for an AMA and demo on Thursday, October 2nd at 3PM ET. The event is open to all; register here to join!

I’m really interested in getting into what you’re cooking up with the Relational Tech Project (RTP), but before we do, can you share a little bit about your respective journeys into this work?

Josh (J): Deb and I should have met a decade ago. In another version of the world, we did.

In my family’s story, the way to align work and values was medicine. I leaned into that, which brought me to a rural hospital in Malawi. While I was trying to be useful there and doing qualitative research, I met community health workers who blew me away — as people and as neighbors. I didn't have the language then, but now I realize that the shape and form of the social fabric in Malawi had me sensing all these possibilities and a different role for me. So I spent the next 15 years working on Medic with an amazing team, building open source software with and for community health workers.

At the end of that experience (around the time I became a father), I was seeking more alignment between power and stake in the world, so I started doing work in community organizing in the U.S. I worked with gig workers who had dreams about platform cooperatives. I worked with doulas who needed to form collectives, so they decided to practice mutual aid for each other as a way to reconnect. This was a reintroduction to care, not as a technical service delivery mechanism, but as a transformational force in the world — and one of the best answers to how we might reconnect with people around us.

I started to experiment with how I might have my block in San Francisco be a place that was prone to caring for each other. We started with a coffee and donuts hangout in my driveway. My daughter and I flyered every nook and cranny on the block and drew hand-drawn “Go Here” signs to our driveway that morning. The first 40 people showed up, and that sent us on a trajectory of community-building in our neighborhood.

I was also experimenting with a new approach to building tech, just as I was flying to your retreat. My previous brain would have wanted to start building out a platform to support mutual aid and mutual support — to figure out how a platform could support the needs of a bunch of diverse groups in the lowest common denominator way. But on this plane, I leaned into “remixing” the existing tech 12 times over, informed by the local organizers, their contexts, and what they’d shared with me about their visions. People responded while I was flying — the feedback loops that kicked in were intense! I arrived at your retreat in a hopeful moment of experimentation — both in my neighborhood and with new tools.

Deborah (D): My story is also influenced by Africa, specifically Arusha, Tanzania. I spent 4.5 years there working at a local wood and metal shop, helping people build their own technologies to make their lives easier. When I say technology, I mean like a bicycle-powered maize sheller or a wind-powered laundry machine. I wanted to live into a world where people of all backgrounds felt the creative confidence to make their own solutions, instead of assuming they needed to receive outside “aid.”

I noticed that after people made their technologies, similar questions would emerge: Who's going to maintain the technology? Who's going to evolve it? Who gets paid or who has to pay for it? These questions led me down an exploration of what we can broadly call “governance.” How do people make decisions and take actions together? How do they build social fabric in order to make those decisions? How do they trust each other enough to do everything else that’s necessary after the decision is made?

While abroad, I heard about the U.S.’s struggles with social fabric and trust, so I decided to return to where I grew up to explore these questions. I started interviewing a lot of people: local government officials, neighbors hosting block parties, leaders of amazing civic organizations. Through the help of friends, videos, forums, contractors, and kind internet strangers, I hacked some stuff together and tested out ideas with neighborhoods in New Jersey, Louisiana, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

Right before your retreat, I wondered: Maybe it makes more sense to return to my Arusha days and help people build their own tools. Could I help a community build a “local tech stack” of digital communication tools the same way I helped people build their own tools in Arusha? Meeting Josh and Sadev at your retreat — who were exploring similar questions in that moment — felt so fortuitous.

You both mentioned the informal retreat that Connective Tissue hosted back in May — and the opportune moment where you two and Sadev ended up meeting each other. All we wanted to do was bring people together, get y’all to know each other, and, maybe just maybe, create the opportunity to identify shared projects. And, then, literally the first morning of the retreat, you three ended up identifying a shared project! How did that happen?

D: I remember talking to you on the last day and reflecting on the retreat in this state of bewilderment. With these kinds of gatherings, I’m usually the one who spends the whole day walking the Appalachian Trail; I don't often want to “scheme.” So it was very strange for me to meet new people and have my intuition say, “l actually want to be scheming right now.” I remember sitting down after I met Sadev on the first day, and he had alluded to the desire around helping people leverage different tools to build their own tools. I thought to myself, “That's not normally what I hear. That's interesting.” Then, when it became an official “session” at the retreat, Josh was also like, “No, we're serious about this.” I was sitting there — we were literally making a strategic plan with bullet points — and I was like, “What is happening?” But also: “This is fun!”

J: Connective Tissue incubated this thing without knowing it. Y'all leaned into emergence, instead of over-design, and it gave us space for this. I was carrying these questions: “Can tech play a role in this movement? What could that look like? Are we going to talk about it?” So when Sadev put up the poster that said, “What does pro-social tech look like?” I was like, “Okay, let's do this.” Immediately, it felt like we were jamming and riffing: “What's after human-centered design? Maybe it's embodied and embedded design — design that’s in your place, in your body, in your set of relationships, right where you are.” It was like that 100 times over for the first two hours.

Then there was the question: “What do we say to everybody else?” The first thing we did was recognize that, usually in these movement spaces, tech tends to coopt and extract insights to serve the dominant system. We wanted to name that dynamic and say that we are trying to chart a different path of solidarity with you all.

D: When the three of us sat down, there was a shared understanding that we are not always the most welcomed in the room — and for good reasons. Tech has a long history of being built on scaling at all costs and being extractive and exploitive. But it was so special to be with two other people who acknowledge that history, and who still have hope that it can be different. We trust that there are others like us, too. That’s at the core of the Relational Tech Project: How do we give people a third way of looking at tech? And how do we invite these people in?

So you guys have this collective insight at the retreat. But what’s happened over the last four months? What is the Relational Tech Project as it stands today? Do you have any principles or practices that underpin your approach to relational tech?

J: We see relational tech as a broad field that’s part of an even broader movement — hopefully, a big upswing in new ways of being and doing in community. The Relational Tech Project is a nonprofit that is stewarding a new commons where local builders can learn, share, and remix tools as they work to cultivate local, healthy relational soil in their communities. Our thesis is that we need healthy relational soil, and from that, a bunch of good stuff can take root and grow.

One of our core ideas is that we can build stuff using technology that deepens our relationships with the people around us. This contrasts sharply with the status quo, where we wait in our homes for other people to build stuff for us and technology is seen as a replacement for relationships. It’s undemocratic and we’re treated as if we don’t have any agency. We’re trying to bring people together with others who are near them to co-create and share stuff that meets their needs.

D: We need to shift this paradigm from “building for” to “building with.” We are capable of building for ourselves and with our neighbors. This requires an internal mind, heart, and soul shift in how we view our relationship with technology. To do that, we take inspiration from good ole’ Alexis de Tocqueville’s phrase “habits of the heart.” What are the habits of the heart we need to practice to shift our relationship from being consumers of technology to being producers of technology? Some of those involve starting with relationships, embracing the uncertainty, and holding in our hearts that if there is conflict, that means someone cares. How do we craft the spaces for us to hold the messiness and wonderment that accompanies our uncertainty, so we can feel safe enough to get creative and weird and try new things? We all can be relational technologists; RTP is an invitation for people to tap into that part of themselves more deeply.

I’m assuming you have some examples of what this looks like in the world, already.

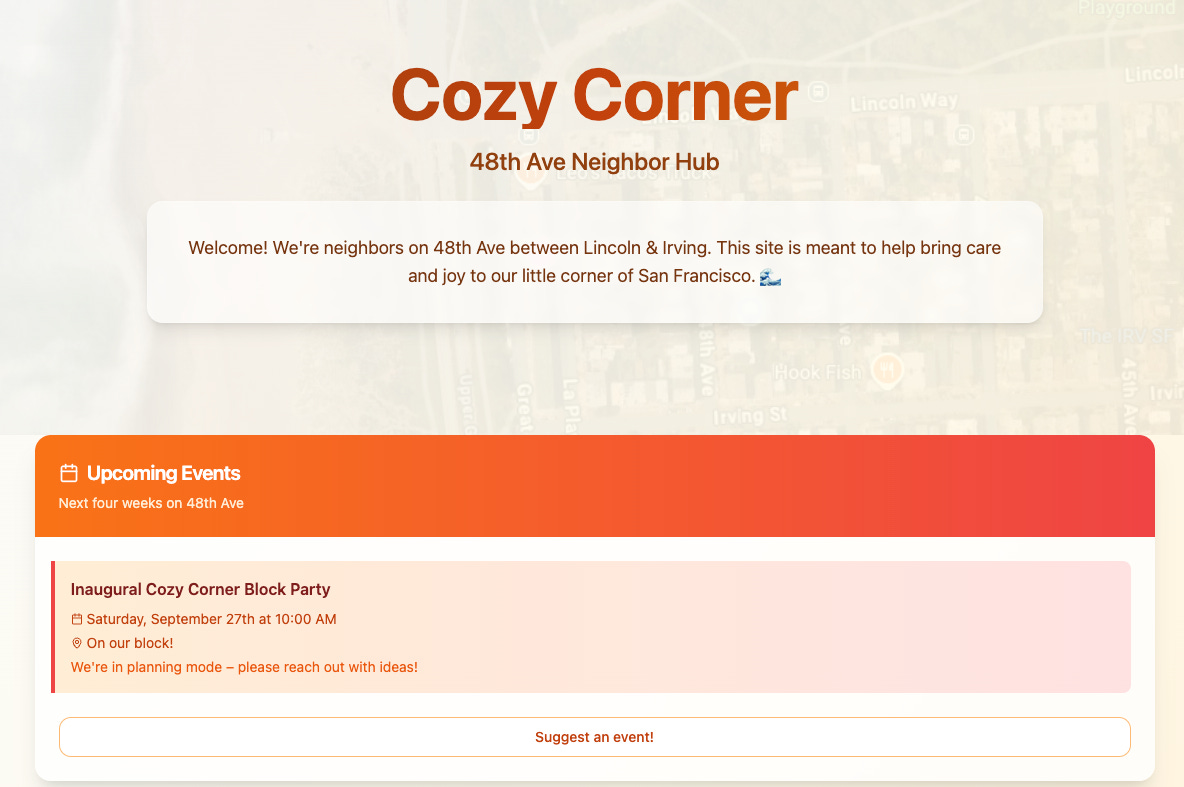

J: I’ve been building technology in my neighborhood, SF’s Outer Sunset. After our first neighbor gathering, I created a neighbor hub; the simple idea was we'd use that to plan our next party and to support each other. The first thing we did with our neighbor hub was a free street cleaning reminder service so people stopped getting tickets. Then we created a block party planner so that everyone could find their role in pulling off a joyful block party in our neighborhood.

A few weeks ago, I was at a birthday party, and my friend said, “I bought all these birthday party supplies and they should not just sit in my garage. They should be shared with people here instead.” That night, we built a local supplies sharing site, and then I texted it to my friend, and his response was, “Holy shit! You built it?” Then he asked, “What if it did this?” Feedback loops kicked in immediately, and then we spent time together — time we wouldn't have spent together otherwise — dreaming up the feature set, testing some of it out, and sharing it with parent groups who are now using it. We have dozens of examples like this now — some works-in-progress, some live and already beloved.

Building in this way has brought us together with this beautiful network of “relational technologists” — people who are building what we need in community and in place. It feels like the start of a new commons: both a commons as a knowledge base of who is building what and why, and a commons where you form pods and squads with other people who commit to supporting each other. Interestingly, AI is playing a role in assisting with the builds. We want to invest in a public good we're calling the “Relational Tech Studio” — essentially, open source software and open models that let us tap into that knowledge base and contribute back to it. So the tech itself, in time, can become part of the commons.

I know the three of us really appreciated this interview with Doug Rushkoff, where he talks about “making things weird” as a step toward resocializing us. And what y’all are doing strikes me as pretty weird — making tech more participatory, relational, and proximate in its creation and application, rather than a vehicle for commodification and consumption.

J: There’s a wobble to our world right now — culturally, technologically, emotionally — and the wobble doesn't last that long because dominant systems work to stabilize and protect the status quo. Weird can meet weird in the wobble — to build relationships, make plans and commitments, and chart a new course together. Deborah was doing some weird stuff. I felt like I was weird. Then we met each other, and now we're working together as part of this emergent (and weird) community of practice.

I'm “post-platform” in my thinking these days. Why? Because platforms homogenize, and I don’t believe tech should be homogenizing anymore. An alternative to platforms is to support the deep weirdness and awesomeness in communities. That will lead to a pluriverse of tech that's built — I'm excited for us to see what emerges from this process unfolding in a million communities. Won't that be different? And sharing and spreading stuff across communities relationally; that'll be different, too. When we talk about the internet being place-based, or the internet being relational, that sounds really weird. But it also feels really necessary: We need to try something different.

When you say something like “post-platform” tech, you’re talking about a very different relationship to scale. You’re also using words like “remix” and “diffusion,” which I don’t associate with top-down approaches to scale. So what’s your theory of scale in all of this work?

J: People in tech are used to thinking about ratios of one to a million or one to a billion in terms of developers to “users.” With RTP, we are living into a new math, where we are super excited about ratios of one to 10 or one to 100. You may have one initial builder leading a spark, 10 co-creators, and then 100 community members that you're in relationship with. The success of it is not evaluated by size or speed — it’s not about going from 100 to 1000 to 10 million as fast as possible. The success of it is evaluated on relational metrics: Are your needs being met locally? Are you connected to your place? We don't give up scale; there are just different axes and ways to look at it. We can still tap into abundance through networks — it’s groups of hundreds of people who network themselves with agency, consent, and purpose. That’s fundamentally different from a platform organizing us.

D: Tech is able to reach lots of people in the fastest way possible by meeting our surface-level needs — and, to do this, tech is often designed for convenient and frictionless experiences. But, it’s the messiness and friction that generates the weirdness we crave: the energy, creativity, aliveness, and playfulness … the indescribable vibes of experiences where a group discovers together what only they could do in the here and now with this group of people. I also think play and shame are two sides of the same coin. So if something doesn’t feel a little subversive or boundary-testing — like, “Am I supposed to be doing this or not?” — then it’s harder to access that sense of play. It’s less messy, less weird, and less alive.

One area of subversiveness that you guys are getting at is challenging the notion that techies are always “democratizing ____,” when in reality they’re often creating access to context-collapsing, place-flattening tools of mass scale. What you're doing, in contrast, seems to be building agency and participation into the very act of creating technology.

J: Most tech that we've experienced in the last 10 years is designed to help us more efficiently fold into the world as it is. We got energized by “world-building” as a frame: Tech should be part of a world-building agenda, and speculative fiction should be part of what we do with our neighbors. In that frame, the product work becomes “let’s imagine the world together,” and introduces questions like, “What role could a tool play in this world?”

D: Relational tech is a physical artifact that people can interact with. When you build something concrete, you can look at it and engage with it and invite others to engage with it, too. You can practice your agency in this small way with your neighbors — alongside others doing the same thing — and realize you’re in a shared dream, building a world together.

J: Sam, you have actually been doing this with the simple microgrant tool that we’ve built! Your Google Docs, our message exchanges, our emails — it's all conversational, and most of what I'm doing is bringing your vision into the code. It’s directly informing the thing that your subscribers are interacting with through your newsletter network. I’m a reader, and I might say, “I want to do these microgrants in my neighborhood, and I have a vision for what it should be like.” I’ll start with the Connective Tissue one, but I know it should be different in XYZ ways, so I tell the code to be different in those ways to align with my vision. Once it’s real, I’ll be at my next house party and I’ll show it to all of my friends because I’m excited about what it could mean for the way our community will be six months from now. My neighbors are going to have a bunch of ideas, and all of a sudden, we're co-creating this thing. Then, when I launch it, it's not from a cold start; instead, we all get to try the thing we made together. That’s relational remixing.

You recently described the question that grounds your work as, “What kind of home do you dream of leaving for your descendants?” Take us ahead a generation or seven. What’s your vision for the kind of home relational tech leaves for your descendants?

D: I embrace the phrase made famous by Deng Xiaoping: “Crossing the river by feeling the stones.” It feels like I am slowly crossing this generational river — multiple generational rivers, really — by feeling the stones, one at a time. I have a broad sense of the vision of a world where many worlds can exist, where everyone feels like they have the agency to shape their worlds as part of that bigger world, together with others, humans and beyond-humans. In this world, they have the space to listen to what the living beings around them are saying, but also the spirits, the ancestors, and the descendants. I want everyone to feel that spaciousness.

J: I found myself living on a block where my kids and their six cousins will also live for probably the next 30-plus years. That triggered a sense of responsibility, a sense of possibility, and a personal call-to-action. I wanted my neighbors to know me and care about my kids, and I wanted to know them and care about their kids. I wanted to feel that generalized reciprocity as tangibly as I felt the concrete I was walking on. Ultimately, for me, it's about cultivating that relational soil: What are we growing from? The nitrogen in there is agency, the water is curiosity, and the sunlight is love. It's got to be a new composition and a new root system, including relational tech, that sets our kids up in a way that we haven't done before. I'm trying to do what I can do now with a lot of trust and hope in them.

Go Deborah and Josh! I really love the process of meeting people where they are, listening to what they're trying to do, big or small, and figuring out ways to create tech systems for them to make it easier. I can imagine all the trust this would build and how it would lead to a deeper interest from people in the neighborhood to dream more and to turn toward each other. This is a very special approach to community building and tech for community. And I lovely the willingness to step into messiness, slowness, and inconvenience that is often what makes relationship and community possible (which has echoes of Maya Pace's recent post "On the Inconvenience of Trash" here: https://trustlabs.substack.com/p/on-the-inconvenience-of-trash).

Lovely!

Amazing and gives me so much hope!