Loving our places in and through their beauty and brokenness

A Q&A with writer and "Uprooted" author, Grace Olmstead

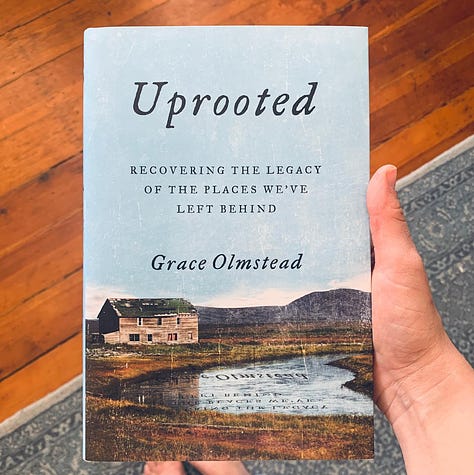

Grace Olmstead is an Idaho-based journalist, mother, and gardener who writes about topics of community, farms, family, and home. Her most recent book, Uprooted, is a deep exploration of the particularities of her hometown of Emmett, Idaho — its history and her family’s history in it, its agricultural and communal ecosystem, its virtues and sins. It’s also an attentive meditation on the tradeoffs between tradition and progress, obligation and autonomy, and rootedness and mobility.

We explore many of these themes from Grace’s writing in our conversation for this week’s edition of Connective Tissue. What does it mean to be a “member” and a “steward” of a place? Why is it important to love our places and communities through the good and the bad, the beautiful and the broken? How can this generation of community writers and practitioners build on the legacy of Wendell Berry?

Though we had only met once prior, this conversation with Grace felt like a chat with an old friend who I had known all of my life. It was warm and funny and challenging and moving — all at the same time. I’m genuinely excited to share it with y’all.

- Sam

PS: If you enjoy this conversation, I strongly encourage you to read Uprooted in its entirety and subscribe to Grace’s wonderful monthly newsletter, Granola. You can also keep up with Grace by following her on what must be one of the kindest corners of Twitter.

How would you begin to describe what “home” means to you?

Our experiences of home are necessarily different. There are a lot of people who grow up on the move constantly, whether because they're part of the military or they're in some other situation that requires a lot of transience. It's often difficult for those individuals to identify any sense of home. Then there are other people who might grow up in one place for the first decade or two of their lives and feel as if that place was a terrible place to live, and they don't associate any feeling of home with that place.

So I actually looked up the word in the dictionary, and I loved this definition and I wanted to read it. Home is a place where something flourishes, is most typically found, or from which it originates.

Most of us associate home with the last part: that place where we originate from. But for other individuals, I love the idea of return: the place where we most typically can be found. I think some of us have a place that we find ourselves returning to again and again, because it is a place in which we feel comfort, hope, and belonging. And that leads to the first part of the definition, which is flourishing. If you think of a house plant, there will be a window or a corner of the house where it actually thrives, where you could say it flourishes. I think we as humans are similar. We're on the lookout for those places in which we find true flourishing, and those are the places that feel like home.

In reading your work, I see a relationship between “home” — as you so beautifully described — and “membership.” Can you explain what you mean by the concept of membership? Why is membership so important to our relationships with place and associational life?

The anthropologist Tim Ingold talks about this idea of life being a webwork or meshwork. Whereas we tend to think of ourselves as hermetically sealed, atomized individuals — determining the way in which we will live, who we will live with, having a very strong sense of autonomy — in fact, we are extremely porous and interrelational and dependent. Your skin is more like a web than it is a single thing. And so everything you are sitting at or near right now is interacting with you in a deeply intertwined fashion. It's impossible to think about humans apart from their connections, their environment, and their relationships. Ingold even goes so far as to say: things are their relations.

If you believe that — if you believe we are in a meshwork, we ourselves are a meshwork, and things are their relations — then membership is just an intrinsic part of what it means to be human and to live in an embodied way. Whether it has to do with the grocery store we shop at, or the sidewalk outside our homes, or the people who live in our homes with us, we are members of a larger whole. We have to be thinking about the ways we are influencing that meshwork for good or for ill, and, also, we have to think about the ways in which that meshwork is influencing us for good or for ill. We're part of it, and with that comes both incredible blessings and, sometimes, incredible harms.

Drawing that answer out a bit further, how do you think about membership as it relates to themes of stewardship, ownership, and agency within communities?

I've been very influenced by both various high church Christian traditions and a lot of Orthodox traditions. I was just rereading The Brothers Karamazov. There's this one scene in which Merkel, this dying boy, has had this realization about the character of God. He's in a garden crying, and his mother is so distraught that her sick little boy is sitting there crying, and she says, “Why? Why are you crying? Why are you sad?” And he says, “Mother, it's for joy, not for sadness, that I am weeping.” Because he listens to the birds, and he says, “I do not know how to love them enough.”

That, to me, is a way of thinking about what it means to be religious that much of the Western world has perhaps lost. At the heart of it is this idea that everything calls for a radical love — even down to blades of grass and singing birds. The world calls for human stewardship and human love in such a way that it would be transformed if we truly loved it the way it was meant to be loved. I believe, very sincerely, that many of the environmental and cultural and social heartbreaks of our time are places in which we've seen an absence of love as it ought to exist in those places.

I think a lot about the relationship between love and attention — love as a form of directed attention and care. Uprooted struck me as a remarkable, beautiful work of attention — be it attention to the nuances of your family’s and community’s history in Emmett, attention to the practices of local farmers, or attention to the intricate details of the soil, land, and natural ecosystem of the place you called home. What role does attention play in your writing? How do you think about the role attention plays in the life of a community and place?

I started working on this particular project because I got a fellowship to write about the decline of small and mid-sized family farms in the United States. Hilariously, when I first started, it did not seem like that large of a product. And then as you begin to unearth the complexity of the various ways in which one might farm — the regions in which various people farm, the crops that they might raise, the markets that they sell to — it was astounding just how big that topic was. So I remembered something that Wendell Berry had written to me some time before: “If you're going to talk about farming, talk about it from the perspective of your family and from yourself as a member of that family.”

That's when I decided I would write about the valley where my family's from. This gave me the opportunity to do what I never could have done if I had been trying to cover the thousands of miles and the millions of farmers that the national project required. In looking at one place — one set of soils, one climate, one geography — I also got to look at one very thorny, complex, and important piece of history. One set of agricultural policies and how they had influenced this one place over time. One town and its growth and suffering and struggles and sins.

Attention of that sort — when we dedicate ourselves to look in one direction for a very long time — it grows love. I love that landscape in that place more than I did when I started, even as (and I note this in the book) I also am much more frustrated with the people who live there and the various things that town has done over time. The two exist together.

If you look at one place long enough — and study its history and its people long enough — you do learn a set of patterns and tendencies that are universally applicable. Whereas some people will say that studying one town has a danger of making you provincial, there's a power and universality to that single-minded attention. We are all human and we are all struggling through similar things together. Just looking at this tiny town of 6,000 people over a couple hundred years — limiting my vision, in that sense — has opened up doors to so many conversations with people from all over the globe. That would not have happened if I had done anything else.

Uprooted also struck me as a book about holding tension. You talked about the tension between autonomy and obligations within communal settings. You talked about the tension between maintaining tight-knit community bonds and consistently expanding the bounds of who belongs in community. You talked about the tension between people who leave for greener pastures (“boomers”) and people who stay to make their pastures greener (“stickers”). Do you see us as out of balance in holding these tensions with American communities today? What would it look like to better hold these tensions within our communities?

Many of the tensions you are describing stem from the fact that we live in imperfect circumstances, with imperfect individuals — and we ourselves are imperfect, all the while. Holding the tension — between the beautiful and the broken, between virtue and vice — is fundamental to loving our places. I've often had the impression that we, as Americans, don't think that a place that struggles with both virtue and vice is worthy of staying in or worthy of our love. We have people in our lives who are complex, who have flaws, who make mistakes, and part of the calling of being involved in those people's lives is to love them through and in those difficulties. But, oftentimes, when we encounter the flaws and the vices of our cities or towns, our immediate temptation is to flee if we can. In fact, places need to be loved in much the same way that we love people — in the midst of their troubles and their heartaches and their brokenness and their injustice — because it's only that complex love that is going to ultimately draw out the good in those spaces.

Emmett, Idaho is a great example of this dynamic. You have these towns and cities that are beautiful, with robust economies, safe communities, and good schools. They have strong neighborhoods and a strong sense of neighborliness. But we also have a history here of institutionalized racism; of de facto segregation; of driving out immigrants from China, Japan, Hawaii and other places; of horrific violence towards the indigenous peoples who lived here; and the list goes on. To live here and pretend like that doesn't exist would be a severe problem. To live here and only focus on those things — to not also think about how we continue to grow and improve and call people's awareness and attention to these things — would also be a problem.

I want to give a vision for how we might love our places in and through the good and the bad, the broken and the beautiful — not just give people this message that, if the place is broken, we should automatically leave. This speaks to the “boomer” and “sticker” issues that I write about: there have to be a set of committed individuals in any given community who say: “This isn't perfect, and we're still going to stick around.” Most of the institutions and places that we come into contact with are going to annoy us at times — they're going to have things about them we dislike. And it is, in fact, a very important aspect of becoming an adult to say: “I'm going to commit to these various things despite their imperfections.”

Three years after writing Uprooted — and after returning full-time to a changed Idaho more recently — I'm curious about how you've experienced coming home. What's met or exceeded your expectations? What's been different than what you imagined?

In many ways, it's been easier than I thought it would be. As I was coming back, I met a local woman through one of my old college roommates, and she invited me into her friend group. She has a book club in which — I kid you not — we meet every month, we read Aristotle and Plato and Jane Jacobs, and we have scotch and we eat cheese, and it's absolutely brilliant. That friendship aspect was honestly the hardest for me growing up, and that was the thing that was solved immediately. I wished I had it for so long, and I never expected to find it coming back to Idaho, and that's been this unexpected joy.

It’s also been lovely being so close to Emmett. We've gone and picked cherries at Waterwheel Gardens the last two summers in a row, and my oldest is now very adamant that it's tradition. We've gone to see Lance Phillips (who I write about) to pick peaches during the peach season. We've been able to make those places part of the seasons we live in.

This past fall and spring, I hosted a couple of “farm days'' with the Dills (who I also write about) for a group of local high school students that I’ve been teaching. We gave them a lecture on local history, taught them about the farm and had them do a farm tour, and then we ate a huge farm lunch together. It was such a beautiful thing to see these kids — who have grown up in the Boise suburbs and who don't have much context of what a farm is or how it works — learn about and experience what it means to be eating things that are grown right here. One of the students who I taught is now working over the summer with the Dills on the farm. His mom texted me and was like, “I didn't know if you knew that he got this job, and he's so excited!” I was so happy. It gets back to this idea of membership — to continue to help people make those connections, to help them know what it means to be a part of this local history, to appreciate some of these farm operations — that has been a gift.

One of your most recent pieces for Plough, “The Farm Woman Speaks,” struck me as both a continuation of and extension beyond what you wrote in Uprooted. How are you currently thinking about the dignity of work for farm women — as well as the dignity of quote-unquote “women’s work” more broadly? What does this work have to teach us about the practice of “good stewardship and care” that you reference in your Plough piece?

The connection between Uprooted and “The Farm Woman Speaks” is in this idea that much embodied work is the work of care and maintenance. If we think about the individuals who work in care — caring for children, caring for farms and animals, caring for those in hospice — a lot of this work is deeply important to the wellbeing of communities and of society. But it's also generally low-paid or unpaid. Often, our culture does not see it as holding much dignity, and many people doing the work of care feel as if they're doing lesser work. Farming is a form of embodied work that, like other forms of care work, can be seen as less intellectual, less demanding, and less important. We need to push back on that point forcefully: embodied work is full of dignity.

I started looking specifically at farm women's work because my great-grandmother was such a huge part of my book project, and the more I studied her life, the more I realized the whole thing would have fallen apart without her. But when people talked about the farm or about the farmer, they were thinking of my great-grandpa. I started doing some digging and came to find that in most farms throughout human history, two spouses have worked together in a true partnership to keep the farm afloat. In many historical farms in the U.S. and Europe, women often brought in more profit than their husbands. Their side of the farming endeavor was usually what we call “value-added production” — things like turning milk into cheese and butter, or things like making beer — which required significant craftsmanship, strength, and acumen. You see those patterns of thrift and craftsmanship throughout these stories of farm women. But I have been writing about this because it's the side of the story of rural America and the historical farm that is perhaps most neglected. It also fits within a larger lens: there is dignity, importance, and worth here that we are at peril of overlooking.

A friend of mine, Leah Libresco Sargeant, has a book coming out soon called The Dignity of Dependence. She articulates a feminism that includes this larger, more comprehensive language of dependence, as opposed to just independence and autonomy. That lens is helpful when applied to this project: no single farm and no single farm community can really exist or operate outside of interdependence and community. So many different parts and pieces make farm communities work and flourish. The work rural women have been doing — often without accolades and without pay — has been essential to this interdependence and flourishing.

I read Uprooted — and your broader writing — to be very much in the tradition of Wendell Berry. Yet, it’s been nearly a half-century since Wendell Berry first published The Unsettling of America. What do you think Wendell has to teach this new generation of communitarian writers and practitioners? How can this generation build on Wendell’s legacy?

Nathan Coulter was Berry’s first book — it came out in 1960, and a lot has changed since. But in our time, we are reaping seeds that were planted 60-plus years ago, back when Berry suggested those seeds might not have a great impact. In the realm of agriculture, we've now experienced what happens when we homogenize, consolidate, mono-crop, spray, and destroy both soil and local ecosystems through processes of industrialized farming. We’ve experienced what happens when we have a collapse of local and regional industry clusters, packaging, processing, and slaughterhouses that connect people to their food systems. During the pandemic, we saw what happens when a fine-tuned, specialized food system becomes brittle and broken. The need for local resilience and complexity and particularity has again come to the fore.

But Berry was talking about this ages ago. A lot that seems obvious to us now was not obvious then. This begs the question: What might seem obvious 50 years from now? What should we be paying careful attention to? What patterns should we be looking for? I think about some of the current studies coming out on social media and smartphones. We need more Wendell Berry voices for this era's technological devices — and for the temptations to step away from embodiment and embeddedness and into this constantly tempting, distracting virtual world.

Of course, work in the realm of agriculture and rural America is not done. What the Farm Bill and many big tech companies suggest is best for rural America is often very different from the vision of local resilience and empowerment that someone like Berry has pushed for. There's still much to be done in terms of talking about what it means to build rural resilience, rural empowerment, and rural health. Berry gives great guidance, but I don't think that we can have any satisfaction when we look at the current state of things. So it almost feels more like a passing of the baton than the closing of a book.

“Embodied work is full of dignity.” Beautiful!

I’m looking forward to Leah’s new book. What a contrast the idea of dependence is to the way I was raised, the way I think deep within.

Thank you for bringing these ideas to the conversation!