Reconnecting with our own creatureliness and wildness

Discovering our wild nature, what it means to live as creatures, and the connection between the body and the earth — and lots of Wendell Berry

“Always in big woods when you leave familiar ground and step off alone into a new place there will be, along with the feelings of curiosity and excitement, a little nagging of dread. It is the ancient fear of the unknown, and it is your first bond with the wilderness you are going into. You are undertaking the first experience, not of the place, but of yourself in that place. It is an experience of our essential loneliness, for nobody can discover the world for anybody else. It is only after we have discovered it for ourselves that it becomes a common ground and a common bond, and we cease to be alone.

And the world cannot be discovered by a journey of miles, no matter how long, but only by a spiritual journey, a journey of one inch, very arduous and humbling and joyful, by which we arrive at the ground at our feet, and learn to be at home.”

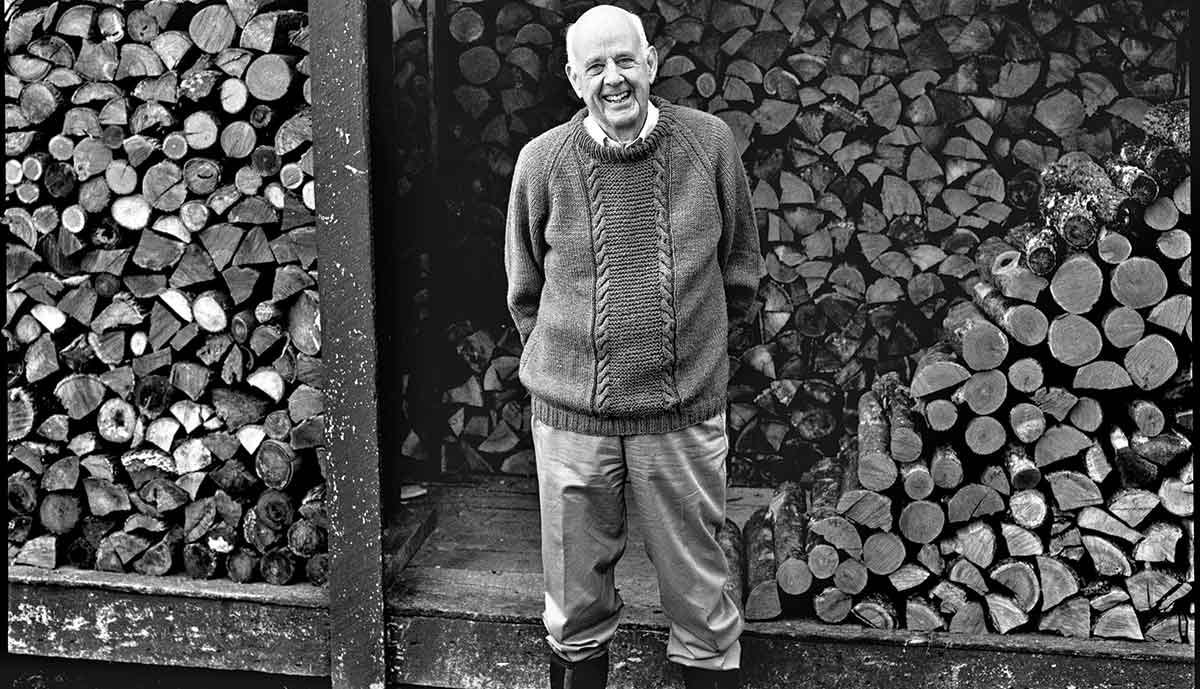

- Wendell Berry, The Unforeseen Wilderness: Kentucky’s Red River Gorge

Be forewarned: Wendell Berry shows up early and often in today’s newsletter. That’s because we’re exploring ecological connection — our connection with our own creatureliness, and our connection with the creatures and wildness of which we are a part. Learning to be at home in the world, as it turns out, takes learning to be at home of the world.

Along those lines, here are a few questions raised in this week’s reads:

How can our care for living things help us discover (or rediscover) the wonder of the world and our place in it?

What does it mean to “live as creatures” rather than “live as machines”?

What is the connection between the spirit and the body, the body and other bodies, and the body and the earth?

How is one group, Outdoor Afro, working to reconnect Black people to our lands, water, and wildlife?

On a personal level, this was one of my favorite curated lists to write up for y’all. I hope you experience the same joy I had reading (and re-reading) these pieces. As always, we welcome your reflections, ideas, and constructive feedback—both on today’s list and the newsletter more broadly.

-Sam

PS: If you want to read a good interview on some of these themes, check out our recent Q&A with Maya Pace here.

The Reads

New York Times - “An Octopus Took My Camera, and the Images Changed the Way I See the World” by Craig Foster

“How strange it is that one silly primate can see itself as separate from all those it shares this world with. What might happen if we remembered we are a part of this wild world — and let that understanding and humility guide every choice we make?”

In this piece, Craig Foster, the Academy Award-winning director of My Octopus Teacher, laments how we have “disconnected from our wild origins” and pleads with us “to get to know nature better, rather than try to ‘save’ her.” He challenges us to resist efforts in the modern world designed “to tame us” and “to dull our minds,” and, instead, imagine the possibilities of “reconnecting with the wild.” To Foster, the answer lies in cultivating attention by “observing wild creatures on their own terms, in their own homes.” In the face of isolation and alienation, Foster’s piece is a call for ecological connection.

Plough Magazine - “The Greenhouse Effect” by Ron Ivey

“What happened in that greenhouse? In caring for those plants, my grandfather found a way out of himself and a way into the world of nature and other people. The structure of the four walls and the discipline of taking care of the plants on a daily and weekly basis reawakened his ability to care about his existence.”

In this moving essay,

(a friend of Connective Tissue) reflects on how a father-son project to cultivate a backyard greenhouse helped bring his grandfather “back from the brink, back to life.” Following an itinerant childhood and a career uprooted by automation, Ivey describes how the experience of “caring for those living things” in the greenhouse enabled his grandfather to rediscover “the wonder of creation and his place in it.” The greenhouse project became the foundation that helped Ivey’s grandfather rebuild his livelihood—finding work again, volunteering with the American Legion and his church, and spending quality time with his family. By the end, his grandfather’s roots had, as Ron put it, “grown deep into the soil of his reality.”The Convivial Society - “Vision Con” by L.M. Sacasas

“…living as a creature is not merely about the embrace of limitations … but rather about the almost inexhaustible depths of experience available to us when we strive for a fullness of presence before the world by embracing the primacy of the body’s entanglement with its immediate surroundings to human experience.”

Reflecting on Wendell Berry’s writings in Life is a Miracle,

explores what it takes to “live as creatures” in a society pushing us to “live as machines.” Part of the answer for Sacasas is to cultivate attention to and become enchanted with the world. This entails attending to “the marvelous specificity of things” — to ourselves, to our fellow humans, and to the enchantedness of the nature that surrounds us all. By living as machines, we become “increasingly incapable of attending to the world.” By living as creatures, we summon “the miracle of being,” which is the “fusion of time and care that we call attention.”→ Read the full newsletter here.

The Theory

The Unsettling of America - “The Body and the Earth” by Wendell Berry

I will not make the mistake of trying to summarize a Wendell Berry essay, much less an essay as uncategorizable as “The Body and the Earth.” Instead, I’m sharing three passages that have stuck with me most—with an invitation to read the whole piece.

On healing and disconnection from the wilderness of Creation

“Healing is impossible in loneliness; it is the opposite of loneliness. Conviviality is healing. To be healed, we must come with all the other creatures to the feast of Creation … Past the scale of the human, our works do not liberate us—they confine us. They cut off access to the wilderness of Creation where we must go to be reborn—to receive the awareness, at once humbling and exhilarating, grievous and joyful, that we are a part of Creation, one with all that we live from and all that, in turn, lives from us. They destroy the communal rites of passage that turn us toward the wilderness and bring us home again.”

On our care for self, others, and the earth

“I have been groping for connections … between the spirit and the body, the body and other bodies, the body and the earth. If these connections do necessarily exist, as I believe they do, then it is impossible for material order to exist side by side with spiritual disorder, or vice versa, and impossible for one to thrive long at the expense of the other; it is impossible, ultimately, to preserve ourselves apart from our willingness to preserve other creatures, or to respect and care for ourselves except as we respect and care for other creatures; and … it is impossible to care for each other more or differently than we care for the earth.”

On working well with our fellow creatures

“It is possible, then, to believe that there is a kind of work that does not require abuse or misuse, that does not use anything as a substitute for anything else. We are working well when we use ourselves as the fellow creatures of the plants, animals, materials, and other people we are working with. Such work is unifying, healing. It brings us home from pride and from despair, and places us responsibly within the human estate. It defines us as we are: not too good to work with our bodies, but too good to work poorly or joylessly or selfishly or alone.”

→ Read the full essay in The Unsettling of America or The Art of the Commonplace.

The Work

Outdoor Afro - Oakland, CA / National Network

Outdoor Afro (OA) reconnects Black people to our lands, water, and wildlife through outdoor education, recreation, and conservation.

OA’s model is driven by their Volunteer Leader Program, which “prepares volunteer leaders to connect and reconnect Black people to nature through planned and guided year-round adventures across the United States.” Today, OA’s volunteer leaders facilitate weekly opportunities to participate in outdoor activities across 60+ cities and 32 states.

You can read a few features on their work in the New York Times, Oprah.com, and Sunset Magazine, and you can learn how to get involved by visiting their website.