This week, we’re sharing our first-ever Q&A with Chase Millsap, a Green Beret and Iraq War veteran turned producer and filmmaker. I’ve known Chase since his time with We Are The Mighty, where he did meaningful work to help tell the stories of veterans and Iraq and Afghan interpreters with nuance and intentionality. Today, he’s the director of Small Town Strong, a documentary about how an Ohio town that has been ravaged by the opioid epidemic has architected its own recovery–with a CrossFit community as the galvanizing force.

Small Town Strong raises so many of the themes that we’ve been thinking about with Connective Tissue. What does it look like to really commit to a place? How can community groups tear down the walls of “us versus them?” What do we owe our neighbors?

We hope you enjoy the Q&A. And if you do, consider watching the documentary. You won’t be disappointed.

- Sam

Sam: Why did you decide to produce this documentary?

Chase: We had no choice. We knew that we needed to tell the story. We really didn’t have a plan, we thought we would shoot enough material to get people interested in a TV show. When we pitched, we didn't really necessarily get a lot of no's. But we got a lot of, “Well, this is really nice. It's nice to see that people are doing this stuff with fitness and recovery.”

But we all knew that there was something deeper. We literally watched a town rebuild itself from nothing into a strong community. Watching that on film, we knew we had something special. And not to get too somber off the bat. But the truth is, you know, we lost one of our main characters, Billy Dever, to an accidental fentanyl overdose along the way. Billy was so instrumental in this community comeback that we just knew we had to tell a story now. So we came up with a plan to film a documentary, shot it ourselves, and went for it.

Who is Dale King? What is he doing in Portsmouth, OH that is so special?

Portsmouth was the original ground zero of the opioid epidemic. Portsmouth’s not so good claim to fame is that they were the place that came up with the pill mills–where you could go in and get a script for opioids legally from a doctor–that was invented here. That was devastating here, because once those pill mills opened up, it was like opening up the floodgates. You had the perfect storm of factories shutting down and people having access to very high-potency opioids. It just went downhill very fast.

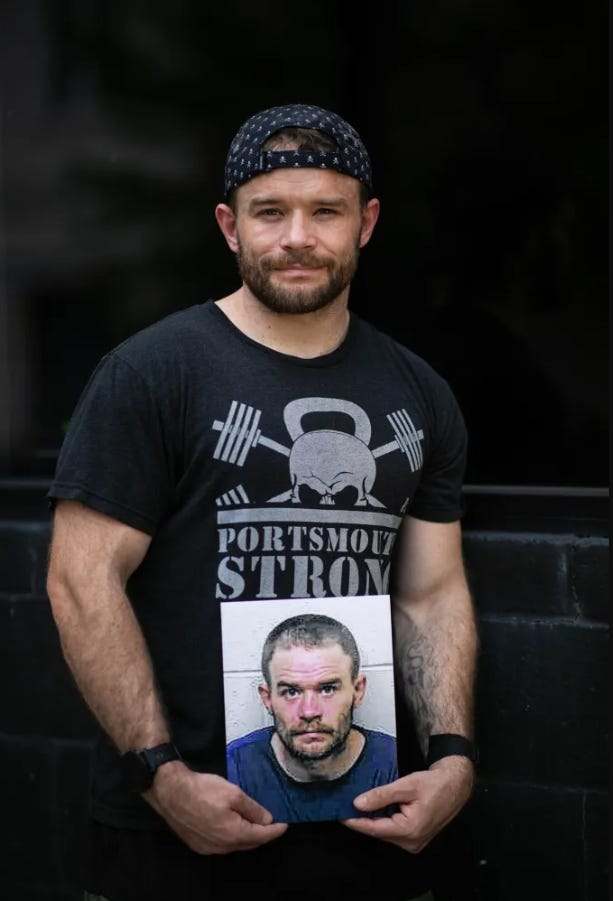

Dale King is a guy who grew up here, joined the Army after 9/11, and did two tours in Iraq as a Special Forces Intel Officer. Then he comes back from Iraq, right around the 2007-2008 timeframe, and he opens up a gym on Saturday mornings called the Pain Clinic. Instead of coming in and getting your oxy, it was about coming in and throwing kettlebells and barbells around and getting in a different sort of pain. And that is what I saw when I came back to Portsmouth, because my wife is from here and had known Dale since high school. We were coming from Los Angeles to visit her parents, and we just saw this change–street corners that you wouldn't be able to walk on that you could now walk on, businesses coming back–and it and it kind of all rotated around this gym.

And finally, I was like, who is this guy? A lot of what he was doing at the gym was adding fuel to the flame. But the flame of community was so much stronger than that. It was this whole cast of characters around town that all had different skills and that all came together around the gym.

Dale’s CrossFit gym is a central focus of the documentary. Can you tell us a little bit about his program for people in recovery? How does it work? How are those in recovery integrated into the broader CrossFit community?

Dale took a lot of stuff he did in the military–including CrossFit–and started bringing it back to his hometown. At first, it wasn’t about recovery, it was about giving people hope. How do you give people the opportunity to workout together in a safe spot doing something hard? You had people from all different backgrounds–older crew, younger crew, all of these people from all over town–all of them were coming into the gym.

And that’s where we met Billy Dever. He was a highly educated lawyer, the chief legal officer of one of the biggest recovery centers in the region and a former addict himself, and he’s an incredible athlete. From there, he had the idea that, what if CrossFit–which is helping people get in shape, have a sense of community, and feel better about themselves–what if that could work for those in recovery? It was really Billy who led the charge of bringing Dale's team into the recovery center in order to offer those classes to people who were going through their in-patient treatment. You get a really good sense of where people have been–like you have people there who overdose on Friday, and now we're doing a CrossFit workout on the following Monday. It humbles you quite a bit. You're like, oh, man, if they could do it, I could do it.

We filmed two or three characters going through their transition in that recovery gym. We started at day 0 right when they came in there, to not only getting out of treatment and getting sober, but to staying sober, getting jobs in their community, becoming leaders in their community, and then competing as athletes. You have the first 90 day window of treatment that is mostly in-patient. Then there is the outpatient, which is where we focused. Once you have the 90 days, you’re clean and you’re starting to figure out your next steps of how you reintegrate into society. It's not too dissimilar from being in the military back home, asking yourself, well, “now, what?” When you’re back, you find yourself in significant challenges – legal issues, job issues – then you need to find an employer who is okay with you to go with your recovery programs and career classes. This can be a hard sell for an employer.

What we were able to film was how Dale not only got his gym and the other businesses that he created to support those in recovery, but also some of the other local employers to open their minds to the idea that these people may be in recovery, but they are our neighbors and we need to help them get back into our community. It wasn’t just recovery isolated from the rest of the community. It was recovery in community.

One of the major critiques of CrossFit is that it can, itself, be addictive. How does Dale consider this in his support of those in recovery? How did you think about this as a filmmaker?

We didn’t set out to make a CrossFit commercial, just to tell stories of people overcoming their addiction with fitness. People were getting through one of the worst times in their lives. We saw a tool that was working. One of the things that was universal, most of the people at the gym look like regular people who are throwing down at a gym. And that’s what’s so special about Dale’s gym: you literally have people from all walks of life, all fitness levels–definitely not your typical CrossFitter. We’re in this little bubble where you see Appalachia America first, then you layer CrossFit on top of it.

This brings up another critique of CrossFit: its financially inaccessibility, especially for middle- and working-class people. How does Dale cultivate such an inclusive CrossFit gym in Portsmouth?

This is what Dale has told me from the beginning: a horrible workout is going to do more to connect people than anything else. You literally have millionaires working out alongside people who live in trailers, that’s just the reality of this gym because of the community they have. And now what you are seeing, when people are coming out of treatment, they are going into Dale’s gym, they are going into other gyms in the community, and they are not perceived as addicts but as members of the community. You’ve broken the stigma of “I used to be an addict, I can’t come here.” Now there are more people who used to be in recovery working out in the community gym than in the gyms at the recovery centers. That really is the sense of community Dale’s cultivated. It doesn't necessarily matter where you came from. It's that you're here now, you're clean, you're sober, and you're healthy. That's all that matters.

You’re telling the story of a place that’s often been defined in the media by what’s wrong with it–I’m thinking Hillbilly Elegy, Dopesick, and the like. How did you approach the filmmaking process to tell a more authentic, complicated story of the place? Did any of your past work with veterans inform how you approached your storytelling in Portsmouth?

There’s no way I’d have been able to tell this story if I hadn’t been able to lean back on my military experience. At the end of the day, it was the ability to endure for a bigger purpose. This was not easy - it took us a very long time. It was like no, we need to keep going. That helped me lead the team in a lot of ways. We didn’t have studio resources, it was the middle of the pandemic, so the production side of it was hard. But we really rallied the community - we had volunteers, people who donated a lot, I even had a 10 year old be my production assistant for a day. The community helped us get the job done.

From a storytelling perspective, I knew we weren’t going down the route of other stories. We had seen enough about how bad the problem was, what we wanted to show instead was hope. One of the biggest things we decided was that the town needs to be a character in and of itself. We need to shoot the town as a character - at day, at night, what it used to look like, what it looks like today. And I think the biggest piece of feedback I've gotten from people who live here is: “I had no idea that Portsmouth looks like that.” That's exactly what we were trying to do: show a different side of a place that you've lived in your whole life.

At the end of the day, because we filmed for four years, we let people tell their own stories and show their own stories. People like Sarah Wilson, who overdosed nine times: you see her transformation over the course of the documentary and her story tells itself. You listen to her own words - how she lost herself in addiction, then she comes out on the other side through CrossFit and community. For me, it was just a matter of helping the audience understand that this is a woman who, yes, has been through addiction. Yes, she has dealt with some hard times. But, in her current state, she's not only sober, she's kicking ass, and she's like helping other people.

There was a really powerful moment in the documentary when Dale says something along the lines of: “You have to care that somebody in your neighborhood is dying. If we can start there, we can start seeing that we all have a responsibility for this whole thing.” I’ve been thinking a lot about the concentration of sacrifice, both when it comes to duties of protection and care. What can Dale’s experience in Portsmouth teach us about what we owe our neighbors?

There are so many things in our current state of our culture that tear us apart. Social media, isolation, a pandemic. In a lot of ways, it’s easier to be isolated than to be in a group. You have to want to be in a community. What Dale and I recognized very early was that, as veterans of the surge in Iraq, you need to literally have a one street block at a time mentality. What Dale honed in on–and what we tried to capture in the film–is that there are little things that you can do. And it may seem overwhelming, but going to a gym, getting a workout, and saying “hi” to someone is super crucial.

When Dale talks about people dying in their community, in a lot of ways the recovery community already knew that. It was about getting people who aren’t experiencing addiction, who aren’t associated with addiction, to get them to care about what is happening here and on their street corner. It takes the person in recovery, and the person not in recovery to unite in order for this to work. Community members are working out alongside neighbors who have been through recovery. And they are kicking ass together and suffering together and they have that immediate bond. Now you have people that are crossing over and helping those that are going through addiction and they are becoming friends. It starts to bridge that gap of “me versus them.” That doesn't exist anymore, and that's the bigger message.

Is there anything else we didn’t touch on, particularly when it comes to community and connection, that you’d like to share?

Dale went away to Iraq and saw in a lot of ways what didn’t work while we were there. Then he came back home to a town that was devastated. He had the skillset to say I could do nothing, or I can make my town better. And he did it. He’s doing it.

What I find so powerful about this story is that the solution didn’t come from DC. Nobody from California, nobody from anywhere else in the world showed up with the solution. This was the town that invented the pill mills, it is the same town that invented a way out of it. There is hope in that. Instead of waiting for someone else to come to you, you can take action in your own community. That’s what Dale is doing. That’s what every one of our characters is doing.