How our online lives shape our lives in community (or lack thereof)

A Q&A with Soren Duggan on the media-community feedback loop, the individualistic online lives of men, and making “progress” against these forces

Welcome to the 400 new subscribers who joined us since our surprisingly popular post last week. Each month, we publish a mix of Originals, Q&As, and Curated Lists related to our theme of “the connections, communities, and commitments that bind us together.” If you haven’t explored our past work, we encourage you to check some of it out. Now, to our newest monthly Q&A …

Soren Duggan is an Army Veteran turned writer and comms leader exploring how our information ecosystems shape our mindsets, culture, and social realities in real life. His Noise Level newsletter is a go-to for me as I try to wrap my head around this bizarre information environment of which we’re all a part.

Soren is also a very good friend of mine — each day, he Signal messages me dozens of ridiculous memes interspersed with some of the most cogent analyses of how the online world is affecting our day-to-day lives. So after countless text exchanges and conversations about the negative feedback loop between our contemporary media environment (his shtick) and our experiences of community in America (my shtick), I realized this would make for an interesting discussion to share in the newsletter.

This interview is a bit of the “greatest hits” from our past conversations (sans the inappropriate jokes). We talk about how the current media ecosystem is intentionally designed to make us spend more time in front of screens and less time with people in community. We talk about the “aggressive individualism” of online life for young men, and what more community-oriented narratives for young men could look like. And we talk about what it could take to begin making progress in this seemingly intractable media reality.

Talking to Soren is always really fun and challenging (in a good way, mostly). I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did.

- Sam

As I was preparing for this conversation, I realized I had no idea how to describe your work. So how would you begin to describe what you’re interested in and what you do?

It’s pretty strange work. I am interested in how our information ecosystem forms our collective mindsets, our social consensus, and our culture. The lightning speed of the internet combined with its social connectivity has created this ecosystem that is both wildly influential in our lives and, somehow, mostly out of our control. I don't think we've fully reckoned with this reality, nor do we fully understand just how affected we are by social media broadly.

Even the word “meme” today symbolizes something pretty inane and funny, so we ignore it. But it's a sociological term that was created far before the internet: a “meme” is defined as the atomic unit of social behavior in a culture — and it’s something that can spread widely. When we're talking about memes, we're not just talking about funny, inane internet pictures or videos. We're talking about the building blocks of a shared culture. We can't just discount those memes because they're silly. Anything that spreads to billions of people and becomes this shared reference point on a species level in a matter of days, sometimes even hours, is anything but silly.

All those interests — memes, the internet’s social connectivity, etc. — brought me to what I do now, where I work in a nonprofit that I co-founded called Shared America. We're still new, but we work with the influencer economy and on digital platforms to amplify alternative narratives to compete with the divisive, socially isolating ones that dominate today.

Soren, you know I tell everyone that you’re one of the top 25 most intelligent enlisted Army guys I ever met — and I really mean that. But how does someone like you end up going from intelligence to special operations to memes and influencers?

That's very kind of you, Sam. Hopefully, someday, I can break into the top 10. We'll see.

You and I are about the same age, I’m 34, and I think this connects back to when I was a kid: our little three- to four-year mini generation has a really different relationship with social media that most others don't share. I was 14 when I got my first MySpace. I was old enough to remember a time pre-internet and pre-social media. But I was young enough to adapt to it as well as anybody can adapt to it (which is, quite honestly, not that well). If you're younger than that, you don't know a world in which social media hasn't dominated the cultural spaces in our lives. If you're older than that, it was a much more disruptive change to the way our society socialized. Watching that change happen from MySpace to Facebook to Instagram to what we have now, was genuinely interesting to me.

Later on, from my vantage point in the military and intelligence community, my interest grew as I watched state actors perform information campaigns online — particularly, watching the way ISIS operated online. They had a very small but effective digital team that targeted, with almost pinpoint accuracy, disaffected young men for recruitment. They recruited young men who had no connection to the Middle East and no connection to Islam. But they reached them online and convinced them, sometimes, to move all the way to Syria to join a fight, or, other times, to be members in their home countries. So that got me thinking about a) how influential social media can be and b) how coordinated digital information campaigns can be used for bad and for good, particularly to proliferate certain mindsets among the public. The difference between a weapon and a tool is how you use it.

Then, it was the 2016 election. I watched Steve Bannon talk about his online strategy and his digital strategy, which involved reaching into these niche corners of the internet, pulling out memes, and sending them down this established pipeline between 8chan and Facebook. It was a pipeline between this deep, weird internet culture, and people who didn't spend a lot of time online but scrolled on Facebook for a couple hours a day. His inspiration was Gamergate — as somebody who has always been fairly online, I knew what GamerGate was at the time — and he identified a culture of grievance that could be exploited online, one that could be leaked then down into more mainstream outlets. His thesis was that politics is downstream of culture, and in 2016, that culture was downstream of the internet. Looking back eight-plus years later, that thesis was correct then, and it is obviously correct now.

Fast forward to 2022, and I got out of the military to turn my focus towards tackling domestic political and social division. But I was still interested in social media as this cultural incubator and the center of gravity of our social zeitgeist. So it just made sense to combine those two things: we need an alternative narrative to counter the rampantly conflict-driven and divisive one that exists online, and there is no better way to do that narrative work than on social media.

I’ve heard you describe a negative feedback loop between our media ecosystem in America and our experience of community in America. How do you think about the relationship between the two? How does this negative feedback loop work?

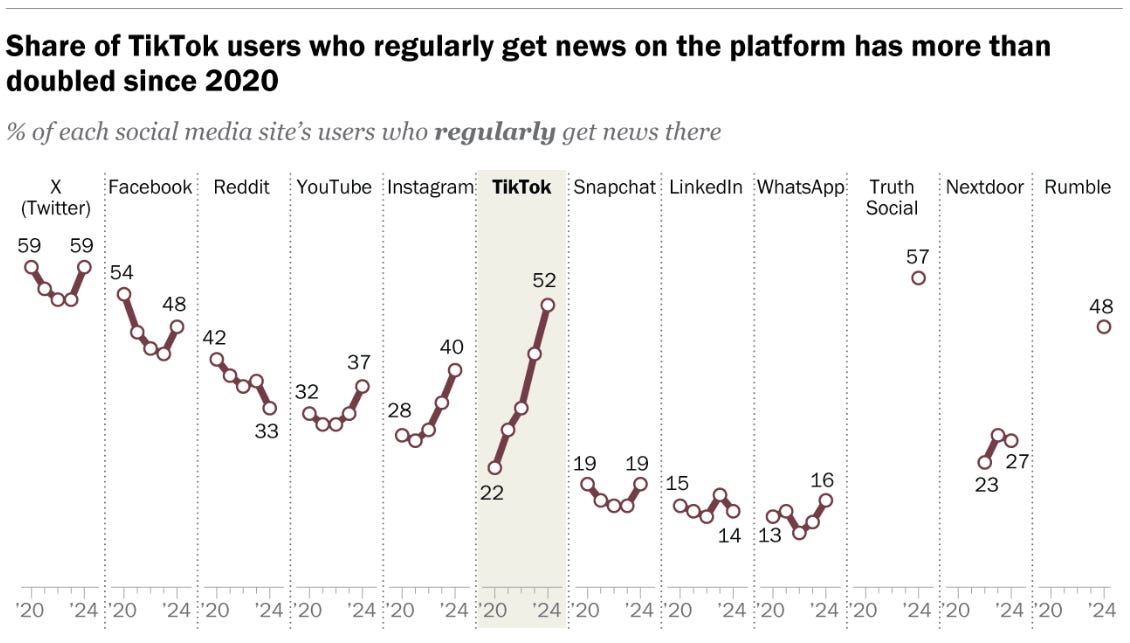

The feedback loop starts with the fact that social media is overwhelmingly negative. The default lens through which it portrays people or events is a radically negative one because the platforms incentivize conflict and emotion as the main drivers of engagement. This causes the people who spend the most time online to generate a very cynical worldview — of the status quo, of the future, of their capabilities, and of one another. It causes people to disengage socially and spend more time online — and that dynamic, alongside the purposely addictive nature of these phones and platforms, creates this feedback loop.

The social isolation that exists now — both due to the internet and other reasons — keeps us at home, where we find ourselves scrolling more and more. This further cements the negative mindset and keeps us in a space, both physically and mentally, in which it is difficult to ever break out of that negative mindset. If the antidote to isolation and division is connection, what's causing our isolation and division is also preventing connection from happening. It's like an autoimmune disease where it starts by convincing you to erase the very solutions that would help address the problem you have in the first place.

I feel like you’re getting at how our media ecosystem contributes to this feedback loop. But can you speak a bit more to the community side of things?

Communities thrive on an association of membership in that community. There's a sort of mutuality to healthy communities. When we erase our in-person tangible life and replace it with a digital one, that association with your community matters a whole lot less. You're now associating with this broad online world that calls itself a “community,” but it isn't really one. For instance, you can frequently scroll on, I don’t know, “home cooking” TikTok and believe you are part of a community of amateur chefs. In reality, you don’t know anything substantial about the other members, nor do you have any proximity to them and their lives. Your only similarities are a shared hobby and your only interactions are, at best, through semi-anonymous comments. We all yearn to have connection and association with others and membership in something larger than ourselves, and I think the internet gives us a false satisfaction of that desire. We believe that we are interacting and associating with other people, but it's not enough. It’s not a genuine or fulfilling enough connection with others.

When we have this desire for connection that community groups typically fill, but people are being pulled toward an online space that is both purposefully addictive and falsely satisfying that desire, our community groups suffer and our broader communities suffer. With many of us staying in our homes and online, we see community organizations and civic organizations struggling to survive. Our in-person participation and our in-person membership are the lifeblood of these community groups.

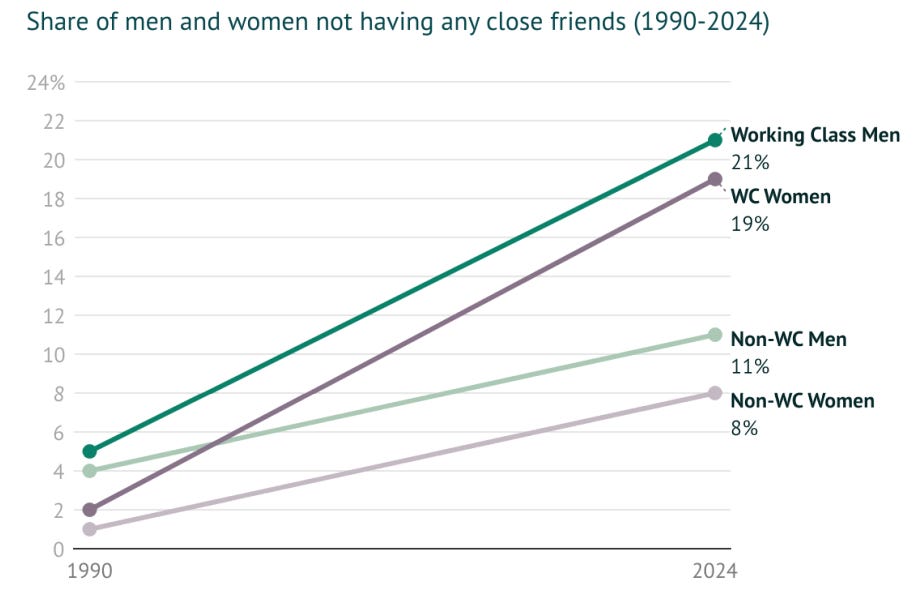

We’ve also had several conversations about how the decline of community, religion, unions, and marriage has left men — especially men without degrees — particularly disconnected. How is this dynamic of civic breakdown and the creeping expansion of online life playing out in the lives of men?

As your research from last year showed, the rates of friendship among men who don't go to college are much lower than men with degrees. If you're starting from a place where you don't have close friends and you don't feel like you are a member of the community you live in, your computer, your phone, and your access to the internet are going to become a way you feel like you can supplement that loss of connection and community. For the young men who feel most disaffected and who have not gone to college and don't have the relationships around them to keep them away from these online spaces — whether it's totally mainstream online places, or they slip into more dangerous, radical online spaces — this negative feedback loop of online engagement and IRL disconnection just self perpetuates.

And it’s not necessarily like these online spaces are bringing out the best in men …

Everything I described earlier about the divisive state of social media is true for young men, but somehow even worse. The content that is made specifically for young men as an audience is particularly reductive and harmful. It’s aggressively individualistic: it does not talk about the importance of having a strong social network or participating as members of their communities, much less leading in their communities. This content can reduce men's self-worth down to the old masculinity tropes of money, power, and sex. And, really, it’s just money: a lot of the content tells them that they can buy the other two if they make enough money.

Not only are they consuming the divisive content that exists for everyone, but they are also consuming a targeted type of content that is getting at the question: what does it mean to be a man today? The answer provided to young men is damaging to themselves and others because of how it reduces their manhood down to the individual and the material. But it’s also particularly bad for community. Success in these online spaces isn't about showing up for the people around you — in your family, in your community, in your friendships — but about how successful you can be, quantitatively, through money and influence.

You and I have often talked about how male veterans, particularly special operations veterans, seem to be some of the most community-oriented people we know while still being perceived as highly masculine. Is there an insight to be gleaned, here, about what a better online and real-life version of masculinity could look like?

In the military and particularly in the special operations world, the idea of operating as a team is essential — you are fundamentally worthless without a team, and you are only as strong as the team around you. So you learn how to function effectively as a team and, more importantly, you learn how these teams can become greater than the sum of their parts. In civilian life, this shapes your mindset about the importance of being an active member of your community.

We need to communicate a definition of masculinity that promotes pro-social behaviors as explicitly masculine. Association with others around you can be masculine. Membership in a community and commitment to that community can be masculine. Having others’ backs — and allowing others to have your back — can be masculine. No one is going to call some Special Forces guy not masculine because he's a member of a team and has to rely on others, right? That doesn’t detract from their manhood, and it doesn’t detract from anyone else’s manhood.

But young men are not being told that. They're not being told that mutualism and intra-group reliance are dimensions of masculinity that can be pursued and can be fulfilling. We need alternative voices and messages out there that are telling young men — who are searching for meaning and purpose and fulfillment — that they can find that fulfillment outside of their homes, their bank accounts, and their bedrooms.

Throughout this whole conversation, we’ve been discussing really big forces in American life — the evolution of our media ecosystem, the decline of community, and the changing roles of men — all of which have been evolving and shape-shifting over several generations. So, I know there is no “magic wand” solution.

But you’re committed to this work, which makes me think you have some semblance of hope. So, I guess I’m still wondering, what does it look like to make “progress” on these forces, however you define “progress?” Who needs to begin taking action? What should they — or we — be doing?

The same capabilities that allow people who want to spread division or profit off division are available to others who want to spread and communicate more positive and helpful messages to bring us through this division. There's been talk for many years — as we debate what the First Amendment means — about this marketplace of ideas. I believe there is a marketplace of narratives and messages, and anybody can create a channel and start talking to the world. It may seem hopeless to try to fight the tide of rampant negativity and engaging reductive content, but it isn't. There are people out there doing it now, we just need more of it. I characterize online content as noise — this deafening noise that combines into something unintelligible. But out of it comes an emotion or a “vibe” that's very affecting. You can affect that noise. You can add to it and create something else.

Is it just more, better content? Don’t things need to change structurally, too?

A good analogy is the anti-smoking campaigns. They were at an inherent disadvantage because smoking is extremely addictive. How do you get people to stop doing something that is both addictive and seen as cool in the culture? The campaign started by creating a permission structure not to smoke and to say “no” to it, and then it evolved to create interesting social barriers to smoking. People were asked to go outside to smoke, so now they could no longer smoke inside and could only smoke in certain areas. Eventually, a line developed in many people’s heads between people who smoke and people who do not. Although you are at a disadvantage online because of the way platforms prioritize conflict over all else, you can still succeed in changing people’s mindsets in a positive way. You can take advantage of the fact that people don't want to feel hopeless and disconnected and divided and angry. They want to feel better.

If you spend a lot of time online, there is no permission structure to believe that things could get better or that things are better. Progress, to me, involves people coming together to create an alternative narrative that helps produce those permission structures — to break down the cynicism about others and our future, and to bring people out of their homes and into their communities. The communication rails are in front of us. We just don’t use them enough.

Thanks for the interview, Sam! Great conversation, as always.

What a great conversation. Another great newsletter!