Connection Grift

Expert gurus, tech companies, political saviors, and national nonprofits threaten to capture our generational moment of civic renewal. But we can push back to channel this connection craze for good.

Connection, so hot right now.

Everywhere I look, words like “connection,” “community,” “civic,” and “belonging” seem to be the dominant concepts of the zeitgeist. I am obviously experiencing some availability bias because, well, I write a newsletter called Connective Tissue. But I also don’t think I’m totally off-base. Our last Surgeon General, Vivek Murthy, made connection the centerpiece of his public platform and “parting prescription.” Our nation’s largest civic institution, the YMCA, is making “Creating Connected Communities” the guiding principle of its next 10-year strategic plan. Some of the world’s largest VC firms, Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia, have made bets on loneliness being an untapped multi-hundred-billion-dollar market. And our preeminent elite media organizations, The Atlantic and New York Times, have each published major stories with titles like “The Anti-Social Century” and “Robert Putnam Knows Why You’re Lonely.”

I’ve begun to call this moment what I think it is: a connection craze. And like the climate and equity crazes of the 2010s and early 2020s, they tend to follow a familiar pattern. After generations of under-the-radar organizing and research, the movement goes mainstream. All of a sudden, new nonprofits and programs emerge to solve these new problems (which, often, aren’t new). Philanthropic funders attempt to create new fields made of these new nonprofits and programs. Politicians begin incorporating new lenses into their political messaging. Policymakers begin applying these new lenses to their actual policies. Startups begin building new products for these new markets. Investors begin investing in these products as part of new investment theses. Journalists begin writing on these new beats, and thought leaders begin thought-leading (?) on them. Slowly, then seemingly overnight, we’re swept up in the frenzy of the craze.

Before I go any further, I want to be clear: Crazes like this usually emerge for good reasons. A core insight or revelation spurs mostly well-intended people to take action to address a legitimate societal problem, such as the widespread degradation of our natural world or the injustices faced by Black Americans. In our emergent connection craze, the 1-2 punch of our mass social media and smartphone experiment followed by prolonged COVID lockdowns — each occurring amidst a 50-plus year decline in associational and religious life — created a collective moment of reckoning on the importance of human connection and community. I’m genuinely heartened by parts of this craze, both because it validates the community-building work that’s defined my entire adult life (take that, Dad!), and because it has created a real generational opening for civic renewal.

But I’m also worried that this connection craze may have a shadow side: connection grift. In the exuberance of the craze, political, social, technological, and cultural entrepreneurs rush in to capitalize on it. These grifters tend to share four key identifiers. First, they often promise to “solve” our “problems” with the tools, practices, models, and ways of being that contributed to these problems in the first place. Second, they often are disconnected from popular constituencies to which they are committed and accountable. Third, they often are able to capture finite resources and power at the expense of individuals and communities. And, fourth, when the dust settles, they often end up reinforcing these problems rather than helping to solve them. Grifters promise us a silver bullet, and leave us a civic life littered with empty shell casings.

I’m writing this piece now because I believe the connection grift has already begun, and it’s a direct threat to our collective project of civic renewal. If we don’t push back, our once-in-a-generation moment of renewal will get captured, money will get wasted, and our communities will be worse for the wear. But I’m also writing this piece now because I believe we still have a window to channel this craze for good: to cultivate a civic future where community members have the agency to shape their individual and collective lives, and where they are enmeshed in overlapping webs of relationships, associations, and commitments to share the joy, wonder, pain, grief, and messiness of the human experience.

In our system where the quick fix and easy buck are rewarded over the long-haul work of durable social change — and where the “politics of spectacle” has displaced the politics of accountability — the line between well-intended opportunism and actual grift is razor thin. That’s why I use the word grift capaciously, albeit imprecisely, in the sections that follow: to show how the opportunistic practices we currently take for granted can do lasting damage to individuals and communities when replicated, craze after craze. My hope is that this piece is a flashlight, a compass, and a companion for the trail: elucidating the big connection grifts we’re currently being sold, providing some direction for what more generative civic possibilities could look like, and inviting you to join me in attempting to stay accountable to the long-haul, generational work of renewal.

Expert Grift: The new friendship “expert” will correct the bad advice that the old self-care “expert” gave.

“There’s this subtle implication that … our need for friendship is an individual-level problem to solve, and that we can only find these things we all deserve for free — friendship and community — if we can pay for it … By virtue of being humans, we know intuitively how to connect and be in community. It makes me mad when it feels as if these ways of connecting have been stolen from us and are being repackaged and sold back to us.” - Elise Granata, “The mysterious, magical, unpredictable human funk of being in community”(2025)

If the 2010s were the decade of expert thought leaders encouraging us to turn inward and focus on self-care, the 2020s are primed to be the decade when these thought leaders encourage us to turn outward and focus on making friends and finding community. They’re already publishing books with titles like How to Know a Person and Find Your People. They will give TED Talks — chock full of pregnant pauses, of course — with headlines like “The Hidden Power of Friendship” and “Stop Networking, Start Connecting” (AI made those up). They will share their “big” ideas on podcasts with hosts who like to whisper gently into their microphones. And some of them will make money — lots of it, too! — from book royalties, speaking fees, corporate consulting engagements, and paid workshops on how to make friends and find community.

This advice to “make friends” and “find community” isn’t necessarily wrong, but self-help expertise like this operates on a fundamentally individualistic, choice-based commercial paradigm that is, itself, part of the problem. Here’s the thing: Making friends and finding community has never been just a choice; it has always required collective scaffolding. As our past research has shown, our ability to access, join, participate in, and make friends in community is largely a structural issue driven by education and class. When thought leaders tell people with limited access to community and no friends to “find your people,” they’re performing the social equivalent of selling get-rich-quick books like Think and Grow Rich and Secrets of the Millionaire Mind. Placing what should be the responsibility of the collective on the individual is a tried and true way to sell books and collect speaking fees. But it is no way to cultivate the communal change or culture of solidarity needed to build a civic life where everyone can actually “find community.”

But experts and cultural entrepreneurs can call us into collective action, and we have powerful examples from recent years to prove it. Jon Haidt’s The Anxious Generation didn’t just tell parents to keep their kids off smartphones and social media, it spurred a movement of policymakers, school leaders, parents, and young people committed to ending the “phone-based childhood.” Richard V Reeves’ Of Boys and Men didn’t just tell men to get their shit together, it created the permission structure for policymakers, institutional leaders, and community members to take action to support men and boys. And Join or Die, directed by Rebecca and Pete Davis, didn’t just tell viewers to “join a club,” it kickstarted a movement of gatherers and joiners committed to cultivating civic “membership” in their local communities. Yes, it’s true that these experts, by virtue of their independence, are still not accountable to the constituencies they helped activate. But it’s also true that they have, directly or indirectly, motivated millions of individuals to strengthen connection in their particular places. And they have all done it by creating the cultural scaffolding for collective action.

Technological Grift Heist: The new tech tools will solve the disconnection that the old tech tools accelerated.

“Tools are intrinsic to social relationships. An individual relates himself in action to his society through the use of tools that he actively masters, or by which he is passively acted upon. To the degree that he masters his tools, he can invest the world with his meaning; to the degree that he is mastered by his tools, the shape of the tool determines his own self-image.” - Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (1973)

Our tech entrepreneurs have assured us that they can “solve” the loneliness they helped cause. Sure, the mass scale adoption of social media and smartphones may have contributed to rising rates of isolation and disconnection, but that’s exactly why we need new “scalable” tools to solve these problems. Sure, many people are scrolling alone on their phones in their bedrooms, but that’s exactly why they need the companionship of AI friends and romantic partners. Sure, venture-backed companies need a 10x-plus return to satisfy their investors, but getting rich and solving loneliness is what we call a “win-win.”

But, as I’ve written about before, this is technological grift in its purest form. Without changing the underlying incentive structures of the tools — namely, the funding, ownership, governance, and business models — tech entrepreneurs are simply dressing up old approaches in new clothes. Since the introduction of television, the business model of media companies has been to capture as much of our time and attention as possible, and convert it into their money. Social media and streaming platforms put this model on steroids by adding attention-fracking features built to keep us hooked. Now, AI companions and chatbots designed to mimic human relationships — all without the friction and messiness of actual humans — promise to make social media look quaint. Of course, the big loser in this competition for our time and attention will continue to be our embedded relationships: with our families, with our friends, with our communities, and with the natural world. Perhaps we should call this a technological “heist” instead; the attention, friction, and relationships that make us human are being stolen before our very eyes.

Another way for our tech tools is possible, though, and the dystopian nature of our current technological reality is galvanizing new alternatives. A culture of resisting the machine is taking root: groups like Offline Club are growing in popularity, and bars like Hush Harbor are experimenting with models for phone-free third places. But there are also emergent efforts to repurpose our tech tools for conviviality. Thinkers like Nathan Schneider and groups like the Platform Co-op Consortium are designing new funding and ownership models for tech platforms to be supported, owned, and governed by their members. The Relational Tech Project is cultivating a network of “relational technologists” committed to building “village” and “neighborhood” scale tools that facilitate in-person human relationships. A future where our tech tools are owned and controlled by members and help strengthen relationships in our communities? That’s a real “win-win.”

Political Grift: The new political savior will clean up the civic mess that the old political saviors made.

“Contemporary prophets of the totalitarian community seek … to transmute popular cravings for community into a millennial sense of participation in heavenly power on earth … It becomes a moral community of almost religious intensity, a deeply evocative symbol of collective, redemptive purpose, a passion that implicates every element of belief and behavior in the individual’s existence.” - Robert Nesbit, The Quest for Community (1953)

Every four years, we’re asked to place our faith in a presidential candidate to be our political savior. In 2008, Obama made himself the face of “hope” and “change.” In 2016, Trump famously declared, “I, alone, can fix it.” Assuming there’s an election in 2028 (what a fun clause to write!), I’d bet that we’ll see candidates running on more explicitly connection-focused platforms. Chris Murphy may run on a platform of combating loneliness and isolation. Wes Moore may run on a platform of promoting service and purpose. Spencer Cox may run on a platform of spiritual and moral renewal. JD Vance may run on a platform of “place” and “heritage.” They’ll collectively raise billions of dollars, in part, on these platforms of communal and civic renewal.

But our national political leaders cannot save our communities, and they know it. When they ask us to put our faith in them as our source of salvation, all they’re doing is seizing on the lack of belonging, meaning, and agency we feel in our day-to-day lives, and translating it to campaign donations and power. The problem is not just how awful [insert last political savior here] was, the problem is also our need for political saviors in the first place. In a flourishing democracy — built on overlapping webs of relationships, memberships, and associations, and where we see ourselves as agents of change in our own communities — voting for national politicians would be the final expression of our will to affect societal change, not the sole expression of that will. But we’re not living in a flourishing democracy; we’re living in a desiccated one. And that means we’re asked to transactionally donate to and vote for our next political savior as if we’re shopping on Amazon, and then pray they act in our best interest.

If Murphy, Moore, Cox, or any other civically inclined front-runner is serious about their civic commitments, they need to completely upend how we do Presidential politics. Imagine if, during the campaign, they ran on an intentionally participatory platform. Instead of concentrating power in the national party, they could commit to rebuilding active membership in local party chapters and committees nationwide. Instead of hosting closed-door meetings with mega-donors, they could host thousands of civic parties across the country. Instead of raising hundreds of millions of dollars for ad buys, they could use the mass attentional event of a Presidential election to redirect money and energy to local non-partisan civic groups. Then, in their first 100 days as President, imagine if they called us into 100 acts of local civic participation. One week could be for potluck dinners with neighbors. The next week could be for block parties, cookouts, and barbecues. Another week could be for neighborhood clean-ups and improvement projects. Yes, all of this is very weird. But if our national political leaders are committed to helping us recover our local civic agency, they may need to apply the Doug Rushkoff theory of change, where “embracing the weird” is the first step toward “triggering agency” and “resocializing people.”

Civic Grift: The new national nonprofits will fix the problems that the old national nonprofits helped create.

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience …” - C.S. Lewis, God in the Dock (1970)

Disconnection and civic decline may be a problem, but worry not: A new suite of national nonprofits are here to save us. Led by professional managers based out of coastal cities, these nonprofits are committed to designing the perfect programs to “scale,” the perfect measures to assess their “impact,” and the perfect “convenings” to “field build.” They’re raising tons of money from big philanthropic funders who are suddenly building “civic infrastructure” strategies and exploring the “connection and belonging” space. And, ready or not, they’re coming to a community near you!

This is civic grift, plain and simple, and it may be the most pernicious grift of all. It wraps itself in the veneer of doing good, hoards significant resources and influence, then proceeds to reinforce practices, models, and forms that have done real harm to communities. By building a new set of national nonprofits led by distant managers, governed by distant boards, supported by distant funders, and validated by distant measures, these social entrepreneurs are replicating the very corporatized, top-down, managerial, and technocratic structures that squeezed the life out of civic life in the first place. And by capturing finite funding for their national organizations, they are directly siphoning off resources that could be going to place-based groups and proximate leaders. Of course, because they are neither embedded in nor committed and accountable to local communities, when connection loses its sexiness and funding dries up, they can just move on to the next craze. Grift, rinse, repeat.

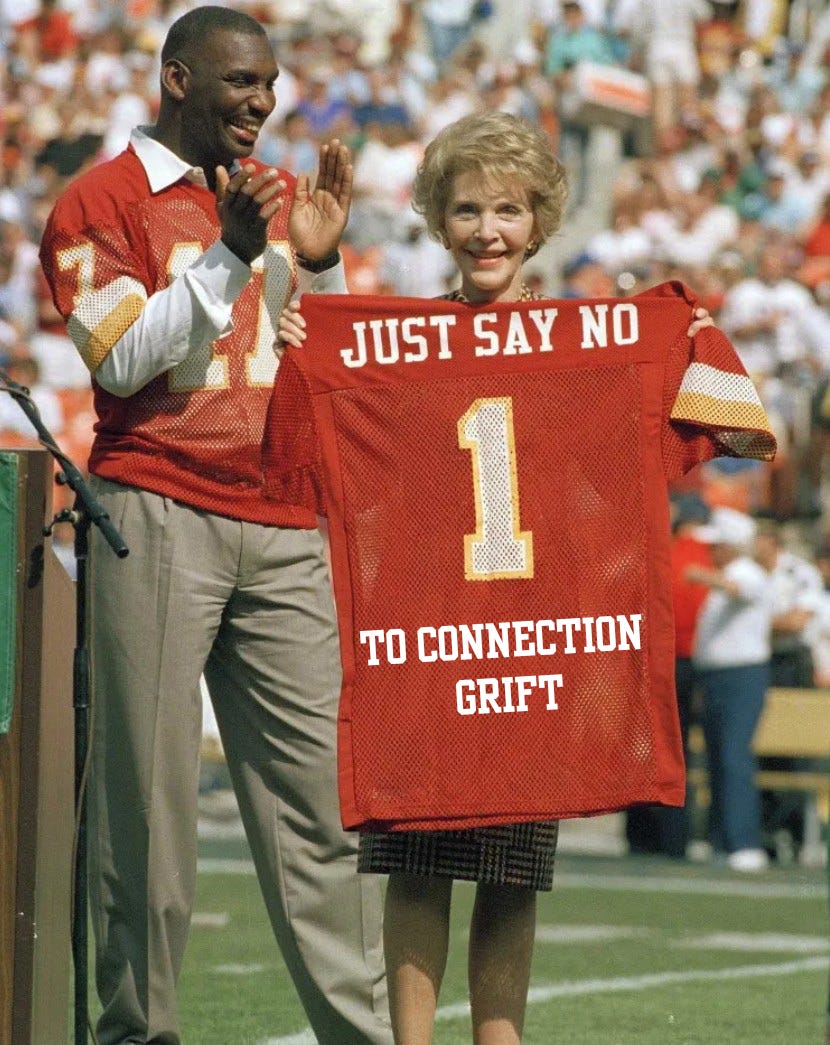

But we can all take a page out of D.A.R.E.’s book and just say no to civic opportunism and grift. Local groups and leaders can commit to reducing their dependency on distant, unaccountable funders by experimenting with ways to realign their membership, revenue, and governance. These same local groups and leaders can also commit to building their own power and influence. Instead of waiting for a national nonprofit or philanthropy to organize them, they can form self-governing networks of locally-rooted practitioners who are connected across place and bound together by a set of shared principles for the civic future they imagine. Funders can commit to investing directly in these locally rooted groups and their self-governing networks — rather than national groups and top-down field-building efforts — and commit to supporting experimentation toward long-term civic realignment and renewal. Make no mistake: This is difficult, slow, generational work. But the alternative is what Wendell Berry would call “the way of ignorance”: continuing to replicate the distant, extractive, and unaccountable institutional forms and models that contributed to the “diminished democracy” we experience today.

Oh my god, this. The networks of trust and social capital that people have worked for decades to build, now getting strip-mined for profit, is a phenomenon that is pissing me off. As I've said elsewhere: "The people profiting from our disconnection now selling their version of "community" are like the mean girl from high school pivoting to the "hey girl!" DM when she wants to sell you her MLM cosmetics"

Your last observation/recommendation reminded me of The Pocket Guide for Facing Down a Civil War which argues that local web/network of courageous relationships among and between us is needed https://www.johnpaullederach.com/2024/07/pocket-guide/